#OscarMustFall: On Refusing to Give Power to Unjust Definitions of “Merit”

Voices for Freedom and Justice.

In March 2015, students across South Africa continued work begun by a generation that sacrificed secondary-school education to fight Apartheid. The Rhodes Must Fall movement galvanized efforts to decolonize curricula. That summer, students across the United States joined the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, raising questions that White and other not-Black people might not see Black victims of police violence because Black perspectives have been erased from education. They also lack knowledge about Black contributions to ending slavery and winning civil rights. U.S. presidents Abraham Lincoln and Lyndon Johnson signed anti-slavery and anti-racism legislation. They did not initiate it, yet they are included in school and university curricula. Black contributions to civil rights and to arts and sciences are not.[1]

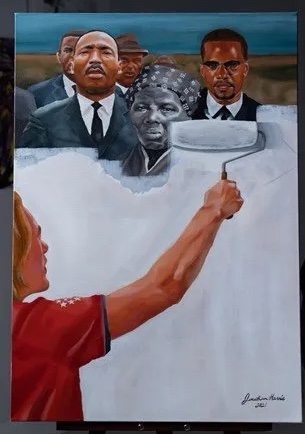

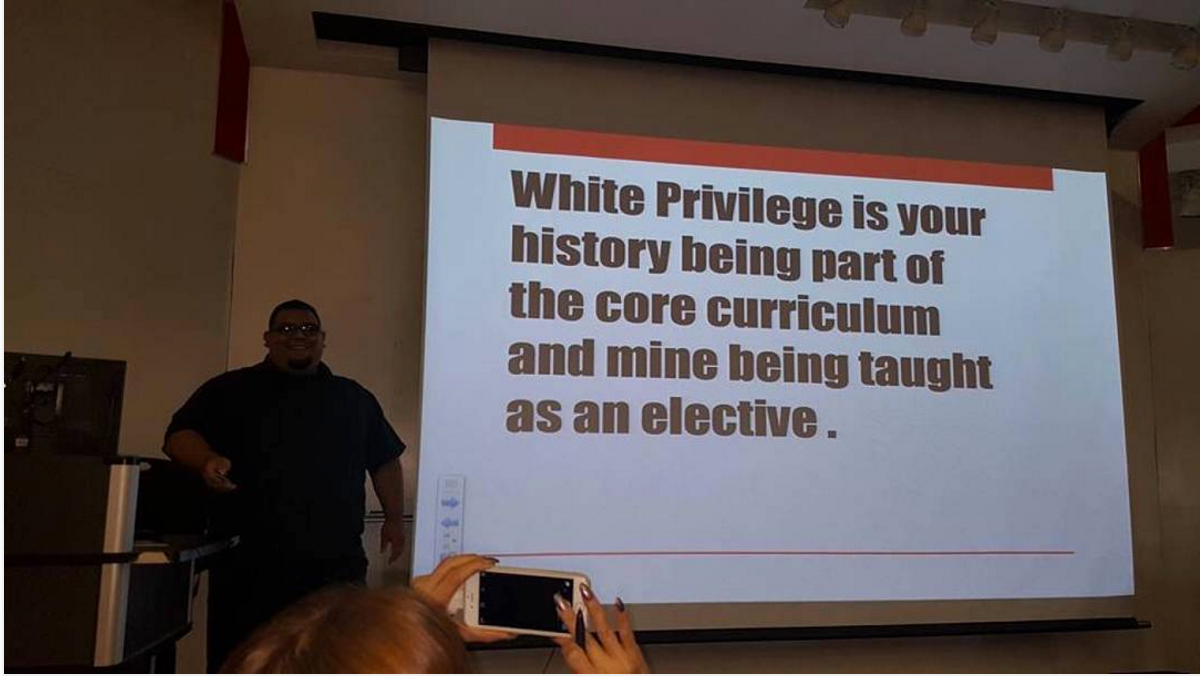

With social media, student protests become memes, asking administrators and faculty a central question: “Why is your history part of the core curriculum and mine an elective?” They cite Simone de Beauvoir, Angela Davis, and Paulo Freire, refusing to accept what Jonathan Harris’s painting Critical Race Theory (2021) makes literal: a whitewashing of Black history. A White man rolls white paint over images of activists Harriet Tubman, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr.[2] Some university administrators struggle to understand connections between “our [university] curricula” and “their [police] violence.” Racism is always elsewhere. Many students and faculty, however, experience and witness palpable, tangible, and undeniable connections between curriculum and violence, often on a daily basis.

This article questions why film educators—alongside critics, distributors, exhibitors, and makers—often describe films and filmmakers as being nominated or winning an Oscar without examining how the awards define merit. The Oscars are one example of White-Western-serving film institutions, including BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) and festivals, including Berlin, Cannes, IDFA (International Documentary Festival Amsterdam), Sundance, and Venice. They must “fall” in the sense that Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni argues Rhodes must fall in “a dual process of both deprovincializing Africa, and in turn provincializing Europe.”[3] Film educators need to provincialize White-Western-serving institutions and de-provincialize a large number of not-White and not-Western ones that define merit in different terms.[4] The Oscars and other White-Western-serving institutions largely define “merit” in ways that disempower and even delegitimize perspectives that call into question their power. Education needs to prepare students for a world that is not only more interdependent, but also more divisive with the rise of nationalism and more dangerous with the climate crisis, income inequality, and pandemics. Since university “diversity and inclusion” schemes can be counterproductive, film educators—graduate teaching assistants, instructors, lecturers, professors—can compensate in courses and curricula.

Institutional responses can add to the problem

elective course. Image shared on social media.

Decolonizing film has a long history.[5] Ella Shohat and Robert Stam proposed polycentrism as a mode to organize the field, which takes on a new urgency after the Cold War’s three options (capitalism, socialism, non-alignment) have been reduced to one: neoliberalism.[6] When U.S. film education emphasizes technical achievement, star system, and popular genres, while ignoring labor conditions and trade agreements, it allows a commercial industry to set the terms. Despite increased screen presence of not-White characters in Hollywood films and of not-Western films in introductory textbooks, unacknowledged bias continues to structure film education, which cannot be corrected with administrator-run syllabi workshops that revamp old curricula. [See appendix for films that most often appear on syllabi.] Adding 1980s Hong Kong and 1990s Bollywood cinema, for example, only make the ongoing exclusion of Chinese and South Asian film history more conspicuous. It avoids confronting criteria that disqualify films and filmmakers from introductions to the field.

Usha Iyer proposes “radical praxis from multiple locations” that rejects “a one-time or a one-size-fits-all fix” for “a proliferation of demands, manifestoes, and countermanifestos that become impossible to ignore,” particularly in universities where we need “an undercommons of killjoys, a coalition of complainers that chip away, course after course, at occupying academic structures.”[7] Locations need to resist being reduced to quantitative data on administrative spreadsheets. Reframing film history as arthouse, Bollywood, Hallyuwood, Hollywood, and Nollywoood films, for example, still excludes the vast majority of perspectives. It focuses only on feature-length narrative films for commercial markets, underscoring how representational diversity and inclusion appears to solve problems but thwarts decolonizing knowledge, especially when faculty are unaware of structural biases within each of these industries.

When such issues are not addressed in education, they disseminate into the world, shaping film criticism, distribution, and exhibition. General audiences use the Oscars as shorthand for merit. Oscar-awarded or nominated films often appear on the covers of introductory textbooks that are unmarked introductions to White-Western filmmaking. Educators can reframe teaching to emphasize that Oscars are not the universal or global definition of merit, but a particular and local one. Rather than an unequivocal accolade, an Oscar can suggest pandering to a White-Western industry or betraying a not-White and/or not-Western community. Such an idea might be shocking to Hollywood élites, but it is one that students need to consider.

Academy apologists define the Oscars as industry awards with holding no obligation towards social injustice. For them, Hollywood is “just entertainment” or “just showbiz”—and everyone “loves” Hollywood films. They ignore unfair advantages and unearned privilege. Hollywood thrives on the illusion of competition, and the Oscars are designed to convince audiences that Hollywood films are objectively better than everyone else’s. The awards even include the category of Foreign-language/International film, which signals merit for films that don’t merit inclusion in the awards’ unmarked categories.

Diversity programs can whitewash the status quo

Academy president Cheryl Boone Issacs claims to expand membership and implement quotas “aggressively,” yet Oscar’s new “diversity” criteria on “representation and inclusion” is inadequate.[8] If the Academy was serious, it would have acted when legal immigration expanded in 1965 or when Affirmative Action became law in 1973.[9] Rehabilitating the Oscars whitewashes impressions. Maggie Hennefeld finds “notoriously racist films” can “easily satisfy the new ‘Standard A: On-Screen Representation, Themes and Narratives’” that “merely requires that a film’s actors or subject matter promote the visibility of an underrepresented group, as if ‘visibility’ were inherently positive.”[10] “Visibility” is representational inclusion that can be tokenistic and even reinforce negative stereotypes. “Simply put, these diversity indulgences are largely a publicity stunt,” Hennefeld concludes; “They’ll be used to exonerate future nominees from accusations of discrimination while providing cover for the Academy itself.”[11]

Change is nonetheless decried. Kirstie Alley called it a “dictatorial” tactic to curb “freedom of UNBRIDLED artistry.”[12] Michael Caine suggested not-White actors need to “be patient” and wait their turn. “Of course, it will come,” he said; “It took me years to get an Oscar, years.”[13] By universalizing his White experience, he imagines racism no longer exists. Charlotte Rampling believed boycotting the Oscars for its racism is “racist against whites.”[14] Catherine Deneuve found Tarana Burke’s #MeToo movement to end sexual harassment—or vigorous and confident “flirting,” as she characterized it—went too far.[15] Alley, Cain, Rampling, and Deneuve have no issues with a system that benefits Whiteness.

Focusing on what the Oscars exclude detracts from what they include—what is meant by “best.” Black actors win when they portray racists stereotypes. As Mammy in Gone with the Wind (USA, 1939; dir. Victor Fleming), Hattie McDaniel was the first to win one in 1940. Her win broke no barriers for others. She was an outlier. Eugene Franklin Wong describes racial segregation and stratification that determine who appears together on screen and who can work together on set.[16] Nancy Wang Yuen describes it as “reel inequity.”[17] “In allowing the film industry and Hollywood to disregard Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964],” notes Latonja Sinckler, “society has allowed these industries to perpetuate a system that favors one race over others.”[18] Segregation and inequality are not solved by representational diversity and inclusion. Hollywood inserts not-White actors in non-stereotyped supporting roles—judges, police officers, and teachers—that serve a White-dominated system in what Sharon Willis calls “guest figures.”[19] Hollywood films appear diverse and inclusive while social structures of Whiteness remain.

1939; dir. Victor Fleming).

with the Wind (USA, 1939; dir. Victor Fleming).

(USA, 1939; dir. Victor Fleming).

Over Oscar’s 93 years, only 14 Black women and 24 Black men have been nominated for leading actor awards. Only six have been nominated as directors. Oscar myths dictate that exceptional not-White and not-Western people will “rise” to its merit. #OscarsSoWhite founder April Reign describes the awards as less meritocracy than popularity contest. Academy members are not required to screen films before voting and award films and filmmakers that reflect their particular ideas about filmmaking and the world. By 2014 with over 86 years and 344 awards for acting, Oscar awarded only 24 (or 7%) to not-White actors; moreover, “Arabs or Muslims are often portrayed as terrorists, African Americans as criminals such as drug dealers, Latinos as criminals such as gang members, and Whites as victims or heroes.”[20] Such statistics are expected. Until recently, Academy voting members were 94% White and 76% male with an average age of 63, that is, “older and more dude-heavy than just about any place in America [sic] and Whiter than all but seven states.”[21] Membership reflects social power asymmetries, but even representational diversity and inclusion among membership is not a guaranteed solution. Some not-White and/or not-Western people are racist, and some women are sexist. Identities and politics align in complex ways. Affirmative Action disproportionately benefits White women because it flattens social difference to allows the most powerful to exploit systems.

Olúfémi Táíwò describes such appropriations and exploitations of “identity politics” as a “tactic of performing symbolic identity politics to pacify protestors without enacting material reform”—what he calls “elite capture.”[22] Institutions use diversity and inclusion most effectively to whitewash their own histories.[23] Educational institutions employ representational categories without challenging disciplinary structures, which can be an counterproductive as hiring neoliberal economists from the former Third World rather than hiring Third Worldist economists. They maintain a status quo.

Feigned ignorance is still racism

Place of liberal White folks in Get Out! (USA, 2017; dir. Jordan Peele).

When asked about “the most insidious and insulting type of racism,” Wendall Pierce mentioned “‘the feigned ignorance’ of white industry members regarding finding talented directors, actors, and writers of color.”[24] Comparably, Rosie Perez considers her “biggest struggle [in Hollywood] has been navigating through other people’s shortcomings,” especially “other people’s bigotry, racism—and specifically the ones that don’t understand that they are bigots or racists.”[25] Hollywood Reporter offers candid insights into what Academy voters think but won’t say publicly. About Get Out! (USA, 2017; dir. Jordan Peele), one confessed: “what bothered me afterwards was that instead of focusing on the fact that this was an entertaining little horror movie that made quite a bit of money, they started trying to suggest it had deeper meaning than it does, and, as far as I’m concerned, they played the race card, and that really turned me off.”[26] (Sexualized racism is a theme that the film actually addresses.) The member’s insecurity over Peele’s film both making “quite a bit of money” and containing “deeper meaning” would be amusing, were it not so racist.

The same member felt uncomfortable that Daniel Kaluuya, “who is not from the United States, was giving us a lecture on racism in America [sic] and how black lives matter, and I thought, ‘What does this have to do with Get Out? They’re trying to make me think that if I don’t vote for this movie, I’m a racist.’ I was really offended.” Academy members do like some foreigners. They admire Winston Churchill, subject of a biopic that year. He is a hero in Britain and villain in India, where his extraction of food contributed to a famine killing millions.[27] Critics, educators, and scholars need to ask themselves whether they feign ignorance that such comments are not part of how Oscar merit is determined.

Such scrutiny is not new. People magazine declare a “Hollywood blackout” in 1996. “The 68th Academy Awards, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg and produced by Quincy Jones, were two weeks away, and the magazine used its audience of nearly 4 million subscribers to announce a shocking discovery,” explains Esther Breger; “Of the 166 Oscar nominees that year, only one was black.”[28] The Black nominee was Dianne Houston for Tuesday Morning Ride (USA, 1995). Jesse Jackson organized a protest outside ABC affiliates, broadcasting the ceremony in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington. He was stigmatized as a troublemaker.

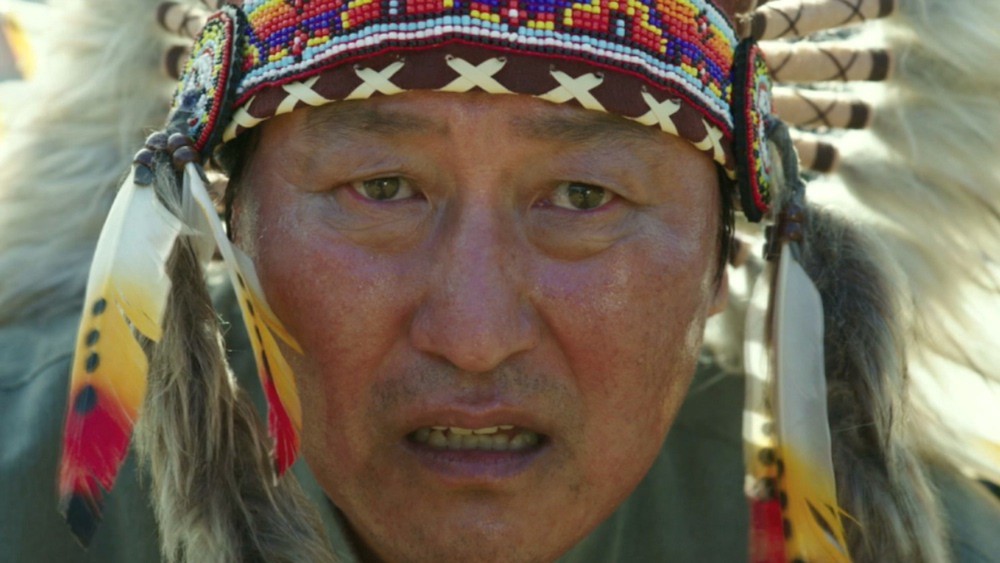

Jacqueline Keeler defines Whites-only nominations for acting in 2016, repeating 2015, as a “symptom of Hollywood’s racism.”[29] She finds “no Oscar nominations for Native American actors or filmmakers or writers” in the award’s 86 years.[30] Oscars recognize Indigenous people when they appear in films by Whites, such as Alejandro González Iñárritu’s The Revenant (USA/Hong Kong/Taiwan, 2015). Because he is Mexican, Iñárritu’s nomination makes the Oscars appear inclusive. The Oscars adore the “three amigos”—Iñárritu, Guillermo del Toro, and Alfonso Cuarón—who, Deborah Shaw notes, make films outside México yet “take on the role of advocates and ambassadors for the national film industry.”[31] They win Best Director constantly, helping Oscar deflect criticisms. “If Cuarón were a white American or European,” noted Jorge Cotte about Roma (México/USA, 2018), “a depiction of an indigenous woman that shored up so many parts of his family’s life would have been even more vulnerable to critical eyes.”[32]

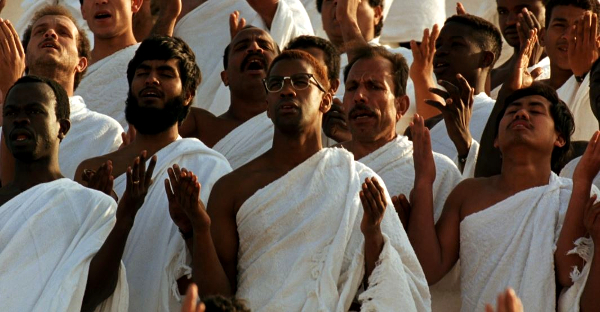

Feigned ignorance extends to not noticing that Oscars rewards Whites and Westerners for appropriating not-White and not-Western stories, such as Gandhi (UK/India/USA, 1982; dir. Richard Attenborough) and Slumdog Millionaire (UK/USA, 2008; dir. Danny Boyle). The films refocus attention back on White filmmakers. Yasmina Price argues White filmmakers make neocolonial films about Africa when trying to critique neocolonialism.[33] Occasional awards go to not-White and not-Western filmmakers for films about White-Western people, notably Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (USA/Canada, 2002) and Zhoé Zhao’s Nomadland (USA, 2020).[34] Feigned ignorance extends to the kinds of not-Western stories that Oscars notices. With its precocious young girl, The Present (UK/Palestine, 2020; dir. Farah Nabulsi) did, much as Wadjda (Germany/Saudi Arabia, 2012; dir. Haifaa Al Mansour) had. Only Arab girls, who appear to act like White girls by defying what White women consider Arab and/or Muslim patriarchy, win Oscar nominations.

“Universal” stories are another form of racism and imperialism

The longest serving presidents of Hollywood’s trade association, the Motion Picture Association, William Hayes and Jack Valenti, inaugurated industry propaganda that Hollywood films are the best in the world because their stories are supposedly universal. John Tomlinson argues that “claims to universality, in short, nearly always relate to some project of domination: it is very rare that the model of ‘essential humanity’ is taken from an alien culture.”[35] Hollywood’s self-definition of its stories as universal functions like a “cultural bomb,” as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o describes “annihilat[ing] a people’s belief in their names, their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.[36] He argues that universalism is imperialism, making its victims “see their past as one wasteland of non-achievement” and “makes them want to distance themselves from that wasteland.”[37] “Amidst this wasteland,” he notes, “imperialism presents itself as the cure.” Chinua Achebe defined universalism as escapism, asking: “if [African] writers should opt for such escapism, who is to meet the challenge [of decolonizing the mind]?”[38]

Appeals to universalism naturalize racism and imperialism. Universalism guides Oscar’s awards for not-White and not-Western films, generally favoring those that tell so-called universal (i.e., whitewashed) stories. In 2020, Bong Joon-ho’s Gisaengchung/Parasite (South Korea, 2019) won Best Picture, allegedly transcending its particularity as Korean or Asian to become universal. Bong won Best Director but was unimpressed, as was Youn Yuh-jung, who won Best Supporting Actress.[39] The Academy recognized Parasite partly due to transnational corporate structures.[40] Parasite’s win raised concerns that it diminished media attention to not-White actors, but Brian Hu argues that Korean American communities created a U.S. market for Korean films.[41] Journalists speculated that Parasite’s win marked a watershed moment, as they had two decades earlier when Ngo foo chong lung/Wo hu cang long/Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (USA/China/Hong Kong/Taiwan, 2000; dir. Ang Lee) won Best Foreign-language Film. Different generations experience their own exhilaration. Hollywood lures with fantasies that the watershed moments are real.

Henry Aray observes the Academy favors “high-income countries,” noting that “50 out of 72 Oscars for [foreign-language film] have been awarded to EU [European Union] countries.”[42] Promoted by Oscar awards to local productions in this category, high-income White-majority states offer potentially lucrative markets for Hollywood films. Aray finds Oscar nominations less helpful in establishing local film industries in medium- or low-income countries.[43] Academy bureaucracy works against not-Western films. Oscar’s bylaws include requirements such as “paid admission in a commercial motion picture theater in Los Angeles County.” Documentary features require seven-day commercial runs in New York. Countries are limited to “only one picture,” giving small states like Germany, France, Japan, and South Korea an unfair advantage over large ones like China, India, and Nigeria. Moreover, transnational funding renders the archaic term “international” meaningless. France’s Unifrance boasts “almost a quarter of the 93 films submitted by the candidate countries” nominated for Best International Feature in 2022 were French co-productions.[44]

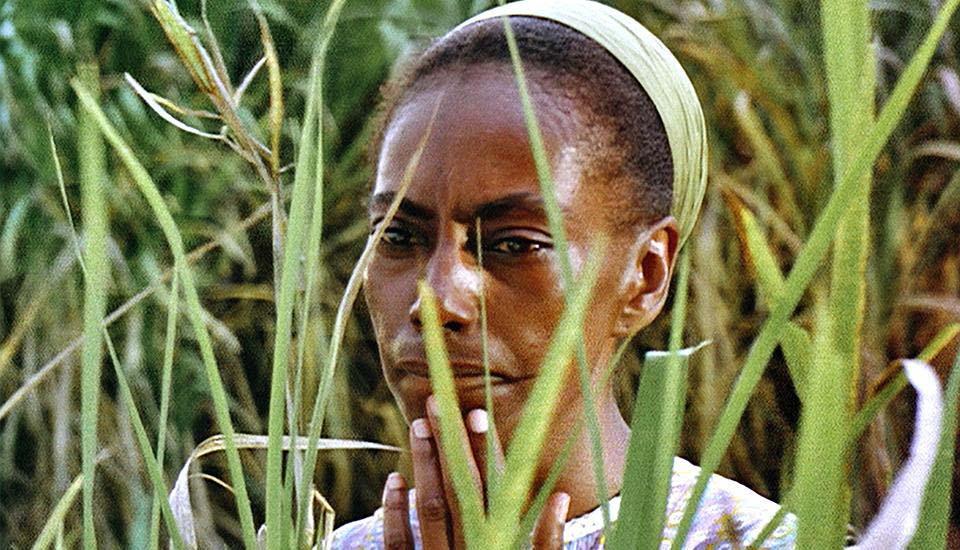

Oscar-nominated films require high production values and stories that do not require understanding by cultural content. Paul McDonald finds Disney’s acquisition of Miramax in 1993 contributed to an “Indiewoodization” of foreign-language film, driven by minimizing risk and maximizing profit.[45] The category “foreign” essentially became a way for Hollywood distributors (aka “studios”) to outsource production. Harvey Weinstein earned the moniker “Harvey Scissorhands” for his extensive reediting of “foreign” films.[46] It might be more useful to teach students about different filmmaking practices and histories. Lampooned by Western critics, Nigeria’s film industry Nollywood is now the world’s second largest.Audiences were fine with lower production values in early Nollywood films since the stories were Nigerian. Nollywood rejected the racism and imperialism of Hollywood’s supposed universal stories, though it also colonizes internally, privileging the “international” English-language films over ones in “regional” languages of Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba, and others.

Not-Western filmmaking is beyond Oscar expertise

“The yearly Oscar ceremonies inscribe Hollywood’s arrogant provincialism,” note Stam and Shohat; “the audience is global yet the product promoted is almost always American, the ‘rest of the world’ being corralled into the ghetto of the ‘foreign film.”[47] Only 22 films without English dialogues or U.S. funding have been nominated for Best Picture. Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project restores (feature-length, mostly narrative) films from around the world, yet his personal “best 125 films of all time” includes only four by not-Western filmmakers, all Japanese, and none directed by women.[48] Scorsese is not an outlier.[49]

Hollywood maximizes profit by protecting its home market (Canada and United States) and opening other markets by aggressively advocating for so-called free trade. After agriculture, petroleum, weapons, and pharmaceuticals, Hollywood entertainment is a substantial portion of U.S. exports. During the 1993 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) negotiations, United States argued that films were just products like automobile and missiles. France argued for a “cultural exception” since film held cultural value and should be exempted from free trade.[50]

At the same time, the U.S. government acknowledges films are more than products, having cultural value as soft power and propaganda. In 1927, the Motion Picture Department within the Department of Commerce was established, so films could act as “silent salesmen” for other U.S. products.[51] Under Will H. Hayes, the Motion Picture Producers and Directors Association (MPPDA, later MPAA) secured State Department intervention in overseas markets in the 1920s.[52] Indeed, the MPPDA’s subsidiary, the Motion Picture Export Association of America, was often called the “Little State Department.”[53] Synergies of industry and state promote and export U.S. national exceptionalism today through Film International and American Documentary Showcase.

Hollywood has prioritized overseas markets since the 1920s, but its films are not consumed because they are “better,” as industry heads insist. Hollywood partnered with the U.S. government, particularly during the 1940s after European and Japanese film industries were destroyed by war. Hollywood opposes protectionist policies, such as national import quotas or taxes. At the same time, the U.S. exhibition market is de facto protected by distributors and exhibitors. Nevertheless, Hollywood discredits foreign competition with belittling epithets, such as “Hollywood on the Nile” (Cairo) or “Hollywood of the East” (Shanghai, then Hong Kong).[54] Filmfare is belittled as the “Indian Oscars”; Premio Ariel, the “Mexican Oscars.” Even fellow Westerners cannot escape Oscar’s shadow: Césars become “French Oscars”; Ophirs, “Israeli Oscars.”

The Oscars prioritizes form over content to train audiences to dismiss films without Hollywood’s production values and resources. Julio Garcia Espinosa argued that “perfect cinema—technically and artistically masterful—is almost always reactionary cinema,” perfectly characterizing Oscar ideas of merit.[55] Prejudice can be internalized. Satyajit Ray criticized Bombay’s film industry for imitating Hollywood. He refused to accept “high technical polish” as merit.[56] His Pather Panchali (India, 1955) was awarded “best human document” at Cannes and applauded as “dramatized documentary” and “timeless humanism” at the Flaherty Film Seminar.[57] These institutions ignored the merit of Ray’s meticulous storyboarding, adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel, and use of Ravi Shankar’s music. They ignored his engagements with Vittorio de Sica, Jean Renoir, and Billy Wilder, perhaps presuming a Bengali filmmaker would not know them, and his references to Indian arts. The Oscars only seem notice not-Western filmmakers when they prioritize legibility to White-Western audiences.

Alternative modes exist. Mahen Bonetti and Carlos A. Gutiérrez programmed African and Latin American films as “South of the Other” for the Flaherty Seminar.[58] They “othered” the Global North. They invited filmmakers whose work exceeded the neoliberal globalist imagination, including Dante Cerano, Ximena Cuevas, Theo Eshetu, Mahamat Saleh Haroun, and Moussa Sene Absa, whose films could not be mistaken for documentary or ethnographic film, as Ray’s Pather Panchali had been. However, the Flaherty Seminar and Cannes are relatively unknown by many audiences, who associate merit with the Oscars. Audiences do not understand that the Oscars’ raison d’être is to promote Hollywood, thus rendering it unqualified to evaluate not-Western filmmaking.

South of the Other:

Oscar “merit” hides Hollywood’s (unmarked) power

Oscar is a colloquial expression for the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ awards for “artistic and technical merit.” Verified by accountants, Academy bylaws are classical Hollywood-style fantasies of meritocracy that exclude the context of inequality. Hollywood myths of competition and meritocracy also undercut organized labor. The Oscars were designed to transform labor into “arts and sciences,” short-circuiting workers’ protection by unions and guilds.[59] In Hollywood’s golden era, studio heads thwarted efforts to regulate the industry. The film industry moved from New Jersey to California in the 1910s was partly a maneuver around antitrust laws. Hollywood later bypassed the Paramount Decree (1948), outlawing the vertical integration of production, distribution, and exhibition. Hollywood is historically anti-competition. The studios worked to camouflage monopoly as competition. “Hollywood films are sometimes discussed as ‘art’ by critics and some filmmakers,” explain Harry Benshoff and Sean Griffin, but “Hollywood film’s merit is chiefly judged by its box office revenue.”[60] Hollywood operates according to myths of market solutions without even acknowledging the state support that it receives. Scholarship shows that taxpayer monies subsidize Hollywood.[61]

April Reign’s #OscarsSoWhite notes disproportionate numbers of White (and Western) nominees, revealing about how Oscars’ definition of merit conceals industry connections and social privilege. Oscar apologists recite industry myths that Oscars bring audiences, launch careers, enhance professionalization, uplift standards—all of which are part of a broader White-Western liberalism that Ijeoma Oluo describes as “centered around preserving white male power regardless of white male skill or talent.”[62][62] Preserving this power, she argues, is a form of ensuring mediocrity since it “limits the drive and imagination of white men” and “requires forced limitations on the success of women and people of color in order to deliver on the promised white male supremacy.”[63] Sarah Ahmed argues that “meritocracy is the fantasy that those who are selected are best,” yet this fantasy “allows the system to recede from view,” and “when a system disappears from view, the assistance given by that system also disappears,” resulting in an unmarked inequality that allows “the selected [to] appear as unassisted by the system.”[64] Merit, then, becomes privilege within membership—which demands compliance and complicity with a system.

Green’s Negro Motorist Green Book — and takes Dr. Donald Shirley (Mahershala

Ali) for a ride in the film Green Book (USA, 2018; dir. Peter Farrelly).

The term “merit” demands such compliance and complicity. Competition allegedly promises opportunity, but most films and filmmakers are excluded from eligibility. Rather than affirming Oscar’s power to define merit, educators can deconstruct this power in introductory curricula. Students need to consider how Oscar defines merit to distract from unfair advantages, such as industry connections, including nepotism, and unearned privilege, whether economic or social. Merit is abstracted and extracted from reality, including the political and social consequences of merit-worthy films that accept racial segregation and gendered glass ceilings. The Oscars define merit in terms of short-term profit without regard for long-term consequences. The Academy recognizes merit in films that reproduce Hollywood’s self-definition of a so-called universal or global model rather than a particular or local style of filmmaking. It is a White-Western serving institution that ensures that Hollywood retains its power.

Oscars reward White saviors

“It’s time for Hollywood to stop defining great drama as White men battling adversity,” argues Mary McNamara, since “in world filled with billions of people who are not white men, they are certainly not the only good stories, not by a long shot.”[65] The Oscars are themselves an exercise in White-saviorism with their “implicit messages of white paternalism,” what Matthew Hughey calls “whites going the extra mile across the color line.”[66] The Oscars presume to rescue Black films and filmmakers from the “obscurity” of Black awards. The Academy cannot fathom that the NAACP Image Awards, Black Reel Awards, and BET Awards have expertise in evaluating Black filmmaking. Such awards mean much more.

The Academy actually delegitimizes Black perspectives. One of its most pointed “snubs” was not nominating Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (USA, 1989) about White police murdering an unarmed Black man decades before Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi founded BLM and Darnella Frazier filmed George Floyd’s murder. The Oscar for Best Picture went to Driving Miss Daisy (USA, 1989; dir. Bruce Beresford), offering comfort to White people that racism is located individuals, who are capable of change, so no need for social reform. The Academy also snubbed Lee’s Malcolm X (USA, 1992) on one of the most important figures in the Civil Rights struggle. When Ava Duvernay was snubbed for Selma (UK/USA/France, 2014) about Martin Luther King Jr., another key figure, Lee questioned Oscar’s relevance. “Nobody’s talking about motherfuckin’ Driving Miss Daisy. That film is not being taught in film schools all across the world like Do the Right Thing is,” he said; “So if I saw Ava today I’d say, ‘You know what? Fuck ‘em.”[67]

When the Oscars overlooks Malcolm X and Selma, it become difficult to defend the Academy. Oscars go disproportionately to White filmmakers, who are imagined uniquely capable of mainstreaming not-White and not-Western stories to wider audiences by “amplifying” (i.e., appropriating) other people’s experiences. Although Satyajit Ray and Ousmane Sembène’s narrative features were “mistaken” as documentary, the Oscars seldom consider actual documentary features made by not-White and not-Western filmmakers. During the 2010s, winners for Best Documentary were films by and about Whites with a few exceptions.[68] Caty Borum Chattoo concludes the Oscars prefer White documentarians with Whites directing 87% and producing 91% of nominated features over the past decade; women (all races), directing 25% and producing 42%.[69]

White-Western women win Oscars for documentaries on “raising awareness” (rather than demanding accountability), “women’s empowerment” (rather than confronting White-Western patriarchy), and “entrepreneurship” (rather than supporting structural change). The Academy ignores U.S. sexism but is eager to recognize violence against women and honor killing in Pakistan and period poverty in India.[70] Awarded Best Documentary in 2005, Born into Brothels (USA, 2004; dir. Ross Kauffman and Zana Briski) established the benchmark for White-saviorism, continuing with Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (If You’re a Girl) (UK, 2019; dir. Carol Dysinger) as Best Documentary Short Subject in 2020. Such films mobilize what Purnima Bose calls “agency in the liberal humanist conception of the subject [that] finds expression in the entrepreneurial self at the heart of neoliberalism.”[71]

Briski).

Carol Dysinger).

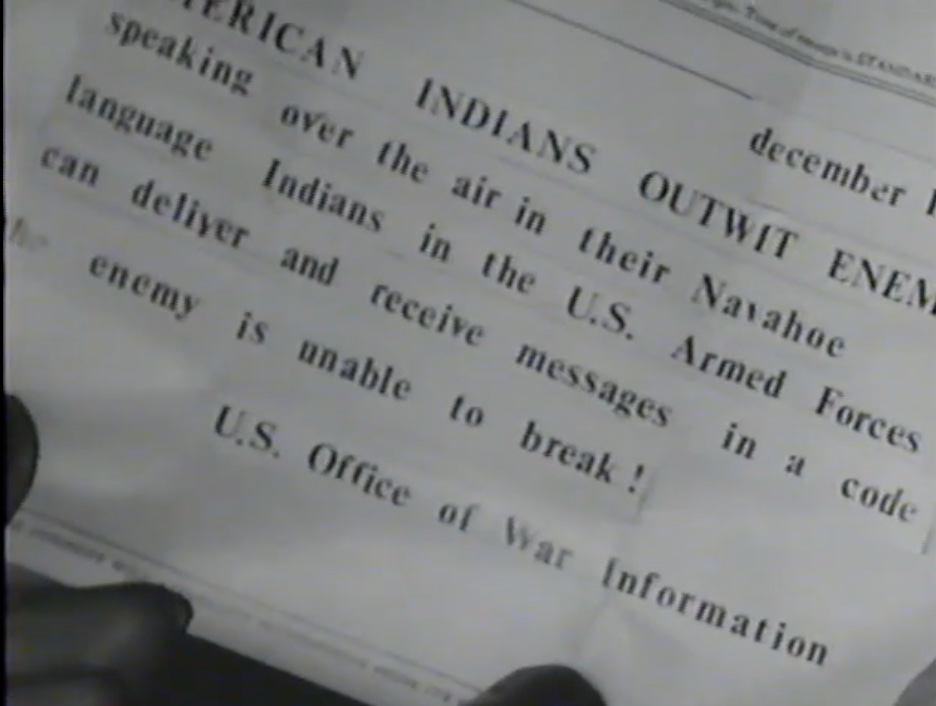

The Academy also prefers documentaries with stories driven by characters and offering closure that brings “catharsis,” a pleasing and privileged feeling that all is or will soon be well, something impossible for many who suffer trauma. The Academy reduces documentary to a consumable product. Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow reject “common-sense wisdom that changing the narrative and telling a different story—or loads of different stories—will be enough.”[72] “Story itself has become part of the problem,” they explain.[73] Some of the earliest Oscar-winning documentaries were wartime propaganda as stories, including The Battle of Midway (USA, 1942; dir. John Ford) and Prelude to War (USA, 1942; dir. Frank Capra).[74]

the old materials of peace) in Prelude to War (USA, 1942; dir. Frank Capra).

Kathryn Bigelow).

White saviorism allows the Oscars to diversify with by awarding White women for making nationalist films. Kathryn Bigelow became the first to win Best Director for The Hurt Locker (USA, 2008), a film so complicit with U.S. militarism that it is overtly anti-feminist. Lila Abu-Lughod, Saba Mahmood, and Charles Hirschkind find spectacularly choreographed endorsements by Oscar-awarded or nominated actors, including Kathy Bates, Geena Davis, and Lily Tomlin, exemplify how Hollywood is coopted by U.S. militarism and resource extraction under the cover of “saving Muslim women.”[75] Bigelow’s film lures audiences to weep over White soldiers rather than question White politicians.[76]

Dignity can be the price of Oscar

Boyle).

In 2019, Elizabeth Méndez Berry and Chi-hui Yang published an op-ed in The New York Times. Its title quickly changed from “We Need More Critics of Color” to “The Dominance of the White Male Critics.”[77] More alarming, its tagline about museum curators and film programmers fighting “white supremacy on the rise” was toned down to “conversation about our monuments, museums, screens and stages have the same blind spots as our political discourse.” Barry and Yang discussed Best Picture winner Green Book (USA, 2018; dir. Peter Farrelly), which received positive reviews from White critics (“a heartwarming triumph over racism”) and negative ones from Black critics (“another trite example of the country’s insatiable appetite for White-savior narratives”).[78] The editorial change echoes what Alex Ruth Bertuli-Fernandes expressed in a tweet about being instructed to “dial down the feminism” in an art class.[79] She posted an image of a dial that could be turned from “raging feminist” to “complicit with my own dehumanization.” Felicia Rose Chavez recounts her own experiences as a graduate student as “White allies warned [her] to ‘tone it down’,” fearing that her “activism” of advocating for “an elective class that featured contemporary writers of color” might annihilate her “professional network.”[80]

Requests to tone-down criticism are a form of intimidation. Green Book producer Charles B. Wessler outright bullied Jenni Miller over her review of the film: “African Americans for the most part LOVE this film. […] I will not go on and on about how wrong you are but you have a big ASS responsibility to write the TRUTH.”[81][81] Green Book exemplifies the toning down rewarded by the Oscars. Brooke Obie found the film appropriated The Negro Motorist Green Book. “Black people don’t even touch the Green Book, let alone talk about its vital importance to their lives,” she noted; “Instead, the film centers the story of a racist White man who makes an unlikely Black friend on a journey through the American south and becomes slightly less racist.”[82] “Uncritical affection for superficially benevolent stories can actually reinforce the racial hierarchies this country is built on,” argue Barry and Yang; “We need culture writers who see and think from places of difference and who are willing to take unpopular positions so that ideas can evolve or die.”[83]

Passage to India (UK/USA, 1984; dir. David Lean).

(UK/USA, 1984; dir. David Lean).

in A Passage to India (UK/USA, 1984; dir. David Lean).

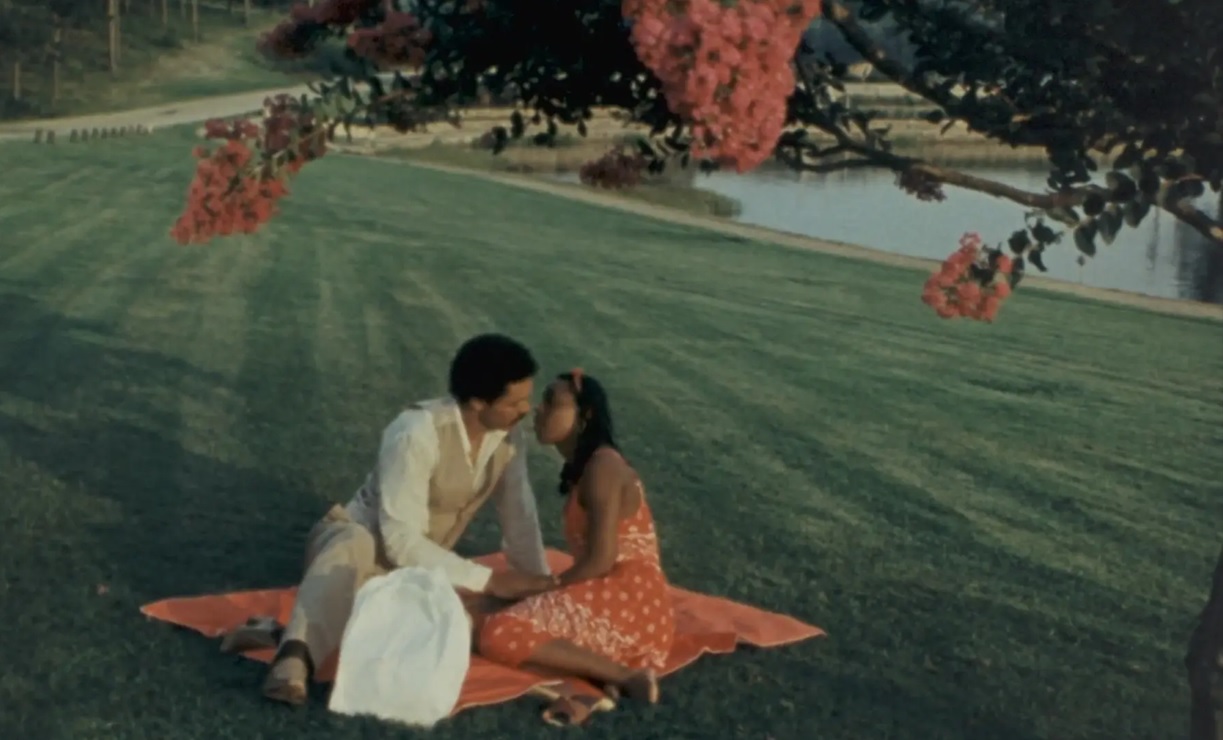

Oscar idea of merit obscures more Black films than it highlights. Noting Losing Ground (USA, 1982; dir. Kathleen Collins) and Cane River (USA, 1982; dir. Horace Jenkins) as “rediscovered” films, Racquel Gates describes Oscar preference for Black pain over Black lives, much less Black joy, asking: “How many more Black films languish on the verge of disappearance, films that may not have been deemed ‘important’ because they cared more to focus on the lovely intricacies of Black life rather than delivering Black pain for White consumption?”[84] She finds: “Black film is still too often assessed for its didactic value, with artistic and intellectual contributions deemed secondary.”[85]

Losing Ground (USA, 1982; dir. Kathleen Collins) is the story of philosophy

professor Sara Rogers (Seret Scott as) and her artist husband Victor (Bill Gunn).

Losing Ground (USA, 1982; dir. Kathleen Collins)

River (USA, 1982; dir. Horace Jenkins) tells a story in Natchitoches Parish

(Louisiana) among the Cane River Louisiana Creole community, early “gens de

couleur libres” (free people of color).

Her assessment echoes what Satyajit Ray experienced. Ray was never nominated for an Oscar. Few Indian films have been: only Bharat Mata/Mother India (India, 1957; dir. Mehboob Khan), Salaam Bombay! (UK/India/France, 1988; dir. Mira Nair), and Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India (India, 2001; dir. Ashutosh Gowariker) in nearly 70 years of considering non-Hollywood films.[86] Despite making most of the world’s films, few Indians are Academy members. Resul Pookutty was invited after being noticed for sound mixing in Slumdog Millionaire, a film that romanticized Mumbai’s Dharavi slum and won Best Picture. Indian filmmakers have made films of Dharavi, including ones who live there, but the Academy favors White perspectives on India.

Before Slumdog Millionaire, Gandhi won eight in 1983, including Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Picture. Ben Kingsley, whose father is Guajarati and whose mother is White, won, but Roshan Seth, Saeed Jaffrey, Alyque Padamsee, Amrish Puri, and Rohini Hattangadi were not nominated. Oscar apologist Emanuel Levy laments that Gandhi beat Tootsie (USA, 1982; dir. Sydney Pollack) and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (USA, 1982; dir. Steven Spielberg).[87][87] and berates the Oscars for what he calls “PC cultural diversity.”[88][88] David Lean’s A Passage to India (UK/USA, 1984) gained nominations and wins. Victor Banerjee was not nominated for his role of the falsely accused sexual predator, but Judy Davis was nominated for her role as the fragile White woman, who only retracted her false accusations after the damage had already been done. Banerjee’s character Dr. Aziz grows from obsequiously trying to please the British to refusing their conditional friendship.

Competition undermines solidarity

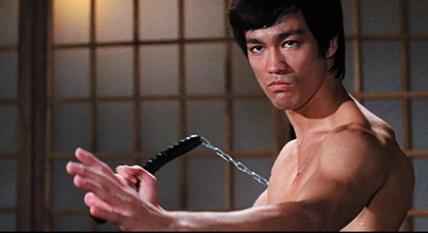

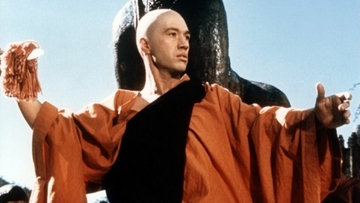

Myths of competition and meritocracy focus on individualism, undermining solidarities needed for decolonization. The Oscars segregate with hierarchies of above- and below-the-line labor—and partition with (unmarked English-language) categories from marked foreign-language/international ones.[89] Hollywood frames collective bargaining to protect industry workers—and quotas to protect domestic markets—as “obstacles” to free competition, yet Hollywood panicked when Hong Kong films topped the U.S. box office in the 1970s. The films starred Chinese diasporic actors, including Lo Lieh, Bruce Lee, and Angela Mao, who defeated corrupt White authority figures. Hollywood responded with imitations, starring White men in yellowface, notably David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine in the television series Kung Fu (USA, 1972).

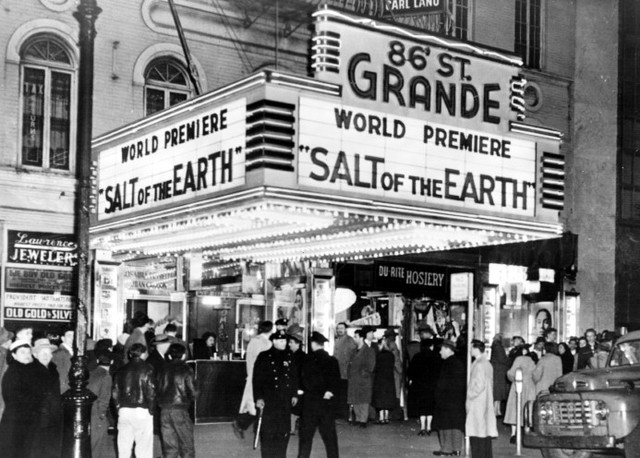

Since “neocolonialism needs to convince people of a dependent country of their own inferiority,” Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino cautioned Latin American filmmakers from imitating Hollywood.[90] They demystified filmmaking as work, not by “artists,” “geniuses,” “the privileged,” but by “the worker.”[91]Organized labor threatens Hollywood. During the era of McCarthyism, Salt of the Earth (USA, 1953; dir. Herbert Biberman) was effectively banned for its transgressive themes of transnational solidarity and gendered equality. The filmmakers were “blacklisted” for association with the U.S. Communist Party, which opposed racial segregation and supported labor and civil rights. The Academy promotes myths that anyone can succeed, that skill and talent matter more than connections and privilege. It prefers exceptional individuals, surmounting obstacles against overwhelming odds to become “our heroes.” Individualism reinforces myths that nothing needs to change except individual mindsets, diminishing the need for collective action to dismantle an unfair system.

Oscar bureaucracy accentuates biases, essentialisms, and eurocentrities. For not-Western films, the primary access to the Oscars is through the Best Foreign-language/International Film category. Countries can nominate one film. Lionheart (Nigeria, 2018; dir. Genevieve Nnaji) and Joy (Austria, 2018; dir. Sudabeh Mortezai) were disqualified for having “too much” English.[92] Oscar’s exclusion of Be with Me (Singapore, 2015; dir. Erik Khoo) was ironic in the context of Singapore’s own “Speak Good English Movement.”[93] Hollywood’s imperial politics are apparent in how few films are nominated from postcolonial states and fewer still from occupied nations.

Puerto Rican filmmakers were ineligible in 2011, silencing their perspectives on U.S. imperialism. Palestinian filmmakers have been made ineligible since only “recognized” states can nominate films. Elia Suleiman’s Yadon ilaheyya/Divine Intervention (France/Morocco/Germany/Palestine, 2002) was deemed a stateless film.[96] The film features a keffiyeh-clad Palestinian woman, who transforms into a flying ninja to defeat IDF soldiers. By contrast, Hany Abu-Assad’s Al-Jannah Al-Aan/Paradise Now (Palestine/France/Germany/Netherlands/Israel, 2005) on suicide bombers during the second Intifada was accepted as Palestinian. Under pressure from pro-Israeli members, Palestine was renamed “Palestinian territories.” The Academy later accepted Abu-Assad’s Omar (Palestine, 2013) about Palestinians coerced into becoming Israeli informants as a nomination from Palestine.[95]

In 2017, Bahman Ghobadi asked the Academy CEO Dawn Hudson to consider the regulation’s erasure of exiled filmmakers, who cannot count upon a nomination by the state they fled.[96] No such category exists today.The Academy seems prejudiced against films and filmmakers from Muslim countries. Oscar only recognized Iranian cinema in 2012, awarding Jodaeiye Nader az Simin/A Separation (Iran, 2011; dir. Asghar Farhadi), which was Iran’s second nomination. Israel has had ten. Mizrahi (Arab) Jews in Israel and diasporic Arabs in Europe became finalists.[97] Arab Muslims in Arab states are not selected. Such omissions contribute to feelings of being presumed incompetent, evident in Arab critics, who associate Oscar nominations with merit, arguing that “with better financial support and fewer restraints, Arab films from the Middle East [sic] could very well be nominated for Oscars every year. And who knows—maybe soon one will actually win.”[98] Other critics understand the Oscars differently. “For what use is an Oscar if it comes at the price of justice, freedom, equality and dignity?” asks Halim Shebaya.[99] When Whites and Westerners celebrate their Oscar wins, they might want to consider whether it comes at the price of someone else’s dignity.

Exceptional opportunities can be institutional opportunism

During the pandemic’s second year, journalists noted that it seemed “like the Oscar nominations never happened” based on what topped Netflix charts, alongside Apple TV, FandangoNOW, and Google Play.[100] The mythical “Oscar bump” of a 30% increase in ticket sales for mid-budget and non-U.S. films from a nomination vanished.[101] Oscar wins for underrepresented groups may do more for Oscar branding than for the actors’ careers. The awards can seem like intuitional opportunism to whitewash history. White actors benefit more from winning an Oscar than Black actors.[102] Brandon Thorp find only “10 black women have been nominated for best actress, and nine of them played characters who are homeless or might soon become so. (The exception is Viola Davis, for the 2011 drama The Help [USA, 2011; dir. Tate Taylor]).”[103] Her nomination for Best Supporting Actresswas hardly an exceptional opportunity.[104] Davis associates acting in the film with betraying herself and her community.[105] Beyond numbers of nominations, roles must be considered.

Almost 60 years after Hattie McDaniel, Berry became the second Black women to win an Oscar for portraying a “conflation of the sexual siren and the welfare queen” in Monster’s Ball (USA, 2001; dir. Marc Foster).[106] The win was symbolic—for Berry and the Academy, but new opportunities did not open for Black women, as the awards continued.[107] Berry’s roles in Batman and X-Men films were unbound of racist stereotypes but disconnected from Black experiences. Like “positive images,” superheroes don’t deconstruct Hollywood prejudice.[108]After becoming first Latina/Latinx woman to win an Oscar for West Side Story (USA, 1961; dir. Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise), Rita Moreno abandoned Hollywood.[109] Anna May Wong and Sabu had done the same back in the 1930s and 1950s. Indeed, Thorpe calculates 13 of 20 nominations for Black men in leading roles “involve being arrested or incarcerated”—and 15 “involve violent or criminal behavior.”[110] Ten have “a white buddy or counterpart,” seven “feature no major black female characters,” and “seven of the characters abuse or mistreat women.”[111] The Academy nominates Black actors who, in words of Miriam Petty, play characters “bound to the destinies of the white people.”[112] Morgan Freeman and Berry won for characters that perform a narrative function of giving White characters opportunities to overcome their individual racism. Structural racism is ignored. The awards define merit in individualist terms, not social ones.

As bell hooks argues, we don’t need diverse representations, but transgressive possibilities.[113] Film educators introduce transgressive possibilities by incorporating ways to deconstruct industry myths. Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg’s compilation film Lip (USA, 1999) unsettles Hollywood’s asymmetrical power allocations to Black and White women. They cut against chronology, avoiding Hollywood fantasies of incremental liberation. Footage underscores how White women increasingly have become false allies to Black women. A clip from For Pete’s Sake (USA, 1974; dir. Peter Yates) show Barbara Streisand’s character open the door to Vivian Bonnell but block her entrance. Opportunity’s door is open, but the way-in is blocked. Black actors are also locked into stereotypes. Bonnell plays Streisand’s “sassy” maid, echoing McDaniel’s Mammy. Moffatt and Hillberg reject the merit of Hollywood’s technically perfect images. The deconstruct with “poor images,” which Hito Steyerl argues reject industry propaganda that image resolution is the marker of quality.[114] Moffatt and Hillberg demonstrate opportunities for deconstructing Hollywood myths via feminist media practices.

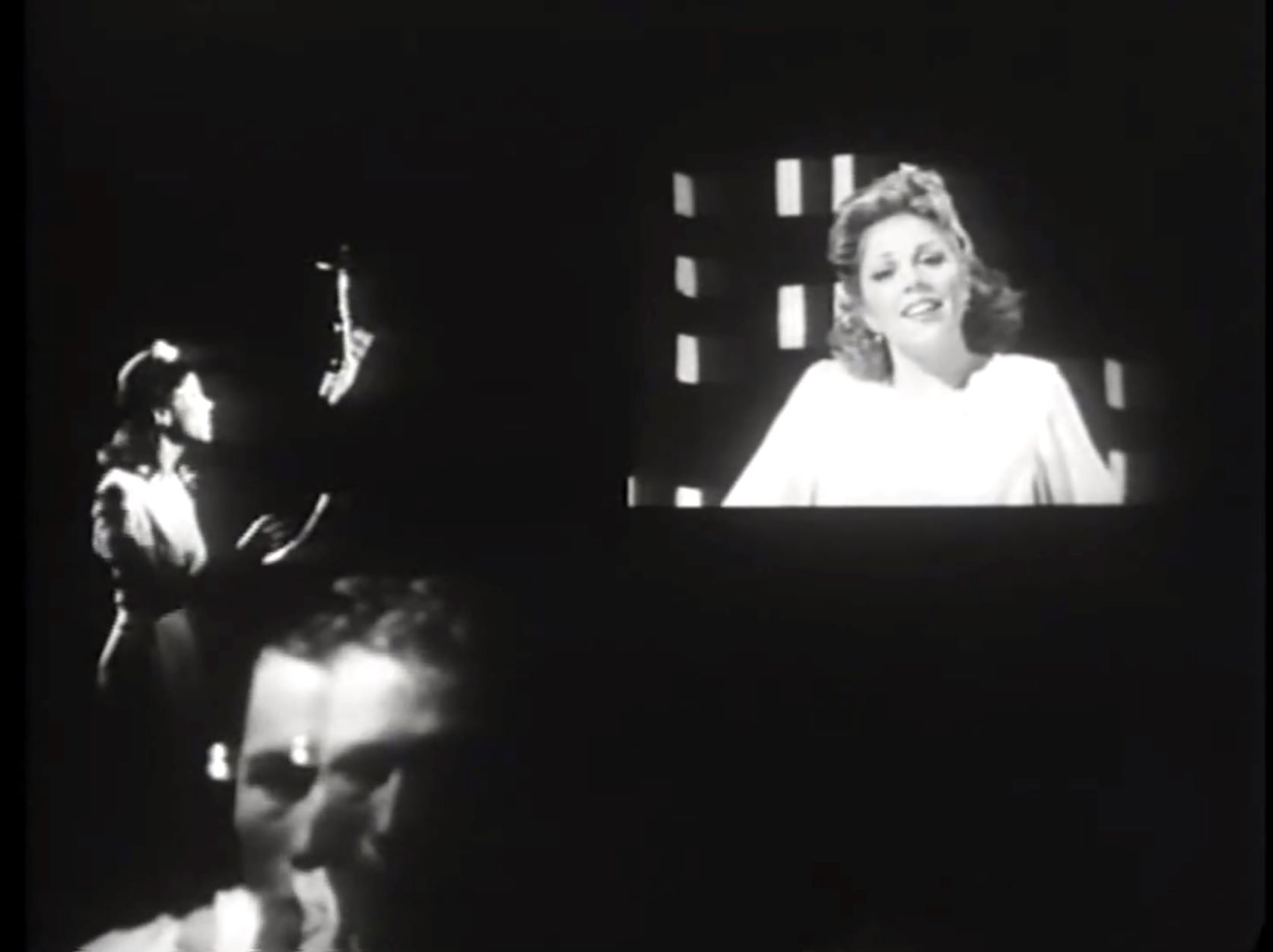

Black filmmakers offer examples of transgressive possibilities. Among the first Black graduates from UCLA’s film school reinvented filmmaking. Julie Dash questions Hollywood’s extraction of Black labor in Illusions (USA, 1982). Set during segregation, Lonette McKee plays Mignon Dupree, a lighter-skinned Black woman, passing as White to work in a Hollywood. Rosanne Katon plays Esther Jeter, hired to “lend” her voice to a star. Dubbing singing voices conceals Black labor required to create the illusion of White talent.[115] The White star is not required to lipsynch to Jeter’s voice; instead, Jeter is required to pitch her singing to follow the White star’s facial gestures. Dupree alone treats Jeter with dignity, offering food and drink after a long day’s work inside the segregated studio, whose production is salvaged by Jeter’s uncredited labor. Dupree labor in passing is self-alienating and must remain unremarked. When Jeter signal recognition, Dupree deflects it. She must endure self-alienation to open the racist system to other Black women.[116] Dupree challenges stereotypes of tragic mulattas.

under the movie magic of a white sound engineer in Illusions (USA, 1982; dir. Julie

Dash).

space of dignity for other Black actors in Illusions (USA, 1982; dir. Julie Dash).

space of dignity for other Black actors in Illusions (USA, 1982; dir. Julie Dash).

(Ned Bellamy) puts his hands on Lonette McKee as Mignon Dupree in Illusions

(USA, 1982; dir. Julie Dash).

A different Oscar, a better role model

Film educators might look to Oscar Micheaux over the Oscar awards for ideas of merit. Rather than working for change inside an existing system, Micheaux invented a new one, opening his own publishing and distribution companies in the 1910s. Even as the White House celebrated The Birth of a Nation (USA, 1915; dir. D.W. Griffith), something the NAACP denounced, Micheaux rejected simplistic “positive images” to offer complex social and cultural analyses of Black experiences. Body and Soul (USA, 1925) starred Paul Robeson, later unjustly criminalized under McCarthyism, in two roles. Micheaux’s films were not perfect. In fact, bell hooks notes his nuance with male characters did not extend to female characters.[117] Film education reproduces Academy definitions of merit as technical rather than social when Griffith’s films are taught over Micheaux’s.

The Oscars are structured around unfair advantages and unearned privileges. Educators can refuse to give them power. “We have to find new ways of external validation that do not predicate themselves on White supremacy,” suggests Roxana Gay.[118] Jack Halberstam praises Stefano Harney and Fred Moten for conceiving refusal as a “first right,” that is, a “game-changing kind of refusal in that it signals the refusal of the choices as offered.”[119] Jada Pinkett Smith refused to gift her cultural capital to the 2016 Oscar ceremony, noting: “Should people of color refrain from participating all together? People can only treat us in the way in which we allow.”[120] She continued: “Begging for acknowledgement, or even asking, diminishes dignity, and diminishes power, and we are a dignified people, and we are powerful, and let’s not forget it.”[121] Spike Lee joined her in boycotting the ceremony.Pinkett Smith attended in 2022 to support her husband’s nomination during a ceremony heavily promoted as a watershed moment with unprecedented numbers of Black faces in front of cameras and behind them. When Will Smith slapped host Chris Rock over a joke about Pinkett Smith’s hair, the Academy attempted redeem itself from inflicting Black pain by inflicting Black punishment.[122]

Oscar has historically been more attuned to White pleasure than Black pain. Due to segregation, David O. Selznick “had to call in a special favor just to have Hattie McDaniel allowed into the building” where the ceremony was held and where she would become the first Black actor to win an Oscar.[123] She was made to feel uncomfortable, so that the Academy’s White members could feel good about themselves for rewarding her portrayal of a racist stereotype. It continues. Haile Gerima was given an inaugural Vantage Award by the Academy in 2021, yet Yohana Desta notes that he was being “fêted” by an industry that he actively opposed his entire career—alongside Sophia Loren from the very country that colonized Ethiopia.[124] He endured ignorance of history—or indifference to his pain—as a favor to Ava DuVernay.

Ryan Coogler made news by refusing an invitation to join the Academy. “I love movies. … For me, that’s good enough. If I’m going to be a part of organizations, they’re going to be labor unions, where we’re figuring out how to take care of each other’s families and health insurance. But I know that these things bring exposure,” he explained.[125] Coogler exposes the price for “exposure.” Hollywood’s gig economy renders life and livelihood precarious for most people working in the industry. Coogler’s refusal to give away his cultural capital is all the more remarkable because he did it in 2021 as the Academy celebrated itself for avoiding another year of #OscarsSoWhite. It nominated its first Muslim (Riz Ahmed) and first Asian American (Steven Yeun) actors, plus two women directors (Emerald Fennell and Chloé Zhao). The Oscars’ outlier year, notes Variety, reveals “the fact that it took until 2021 for the Academy Awards to recognize a widely heterogeneous array of nominees also speaks directly to the deeply entrenched prejudices that have kept people of color outside of the Oscars—and the film industry at large—for so long.”[126] It might be better to ignore the Oscars all together than Oscar Micheaux did.

De-Oscar-izing film education

Adam White rhetorically asks what purpose the Oscars serve.[127]They matter because critics, distributors, educators, exhibitors, makers, and students often look to the Oscars as shorthand for worthy of merit.[128] Women constitute more than 50% of the planet’s population—and not-White and not-Western people constitute most of it, yet their perspectives seldom appear in films awarded Oscars. The Academy might increase not-White and not-Western members, but the criteria of judgement are designed to exclude them.[129] Students often arrive in classes with their entire perception of filmmaking defined by Hollywood and its Oscars.[130] Understanding what the Oscars actually represents and whose interests they actually support is a compelling reason to reject them.

Decolonizing curricula and pedagogy are merely a beginning to actual reparations and abolitions that must take place to address various inequities. When film education emphasizes technical achievement, star system, and popular genres, while ignoring labor conditions and trade agreements, is allows Hollywood to set the terms. The Academy’s technical and artistic merit bulldozes all else (i.e., how the film intersects with the real world). Gone with the Wind and Lawrence of Arabia (UK/USA, 1962; dir. David Lean), both Oscar winners for Best Picture, alongside The Jazz Singer (USA, 1927; dir. Alan Crosland) and The Searchers (USA, 1956; dir. John Ford), have technical merit that is historical, but little social merit that is relevant. Oscar-winners and serial nominees Wes Anderson, Danny Boyle, James Cameron, Francis Ford and Sophia Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg also warrant reconsideration since they fail to challenge the system that guarantees their power. Film education needs de-Oscarizing to prevent future generations like them.

Film education is a starting point for decolonizing film criticism, distribution, and exhibition. By deconstructing the Oscars, educators can deconstruct film education. Much like the Academy segregates and partitions technical and artistic merit from political and social consequences, film education traditionally segregates “production and craft” (i.e., technical and practical training) from “history, theory, and criticism” (i.e., intellectual, contextual, and political training), thereby promoting a particular kind of filmmaking as the only and best one. Film practice and studies can be integrated, so that technical or artistic choices are understood as having political or social consequences.

Integrating studies and practice allows for opportunities to deconstruct industry-driven assumptions about story, character, style, aesthetics, technical skill, production values, and work flow that can make it difficult for not-White and not-Western students to tell their stories from their perspective. Too many classes remain colonizing with untheorized assumptions about “relatability,” “personal vision,” and “proper technique.” Students can be misled with naïve statements that art and criticism are incompatible—that “over-thinking” (euphemism for thinking critically) kills creativity, as though thinking were somehow not creative—and creating was somehow outside thinking. Comparably, film educators can reject business solutions to make curricula more diverse and inclusive. Instead, they can focus on what bell hooks describes as an “oppositional gaze,” which can be trained to recognize other definitions of merit, such as advocating for rights, changing toxic discourses, or locating new role-models.

Why #OscarMustFall matters to everyone

If Rhodes must fall, Oscar must fall—and it is a shared responsibility to help it fall. Given crises that current and future generations will face, merit in activist, community, Indigenous, and other noncommercial filmmaking modes might be recognized. Assimilating to Oscar’s model is an exercise in “disempowerment,” to borrow Felicia Rose Chavez’s term.[131] Film critics, distributors, educators, exhibitors, and makers can contribute in different ways.

Educators might reflect upon their role in perpetuating disempowerment. If students think that an Oscar nomination proves that films or filmmakers from their home culture or country are finally “good enough,” educators can help them see that the Academy is actually not good enough to evaluate such films and filmmakers. Educators can deconstruct such disempowering assumptions as part of the curriculum, requiring White-Western students “to acquire the intellectual and cultural resources to function effectively in a plural society.”[132]

Critics can minimize industry awards and box-office figures, which contribute to a cycle of disempowerment, and champion other models. Juan Francisco Salazar and Amalia Córdova describe how Indigenous media festivals decouple the term “best” from individual achievement and apply it to social engagement.[133] Where mainstream media to focus attention on socially engaged film, it might embolden distributors and exhibitioners to select more. Makers can stop defining themselves by festivals and awards. Instead, they can define themselves by the content of their films—and the debates into which their films intervene.

Hollywood already saturates media with press releases and promotional materials, so there is no need for any of us to disseminate manufactured buzz. Instead, we can focus on evaluating films, not as escapist entertainment, but as engaged responses that aim to shift larger public discourses on social issues of climate crisis, neoliberal economics, populist nationalisms, private wars, public health, religious fundamentalism, single-issue feminism, and systemic racism. We need to become advocates and allies for future generations, whose world will be more precarious than our own. #OscarMustFall is not to say that Oscar should be destroyed but that it should be decentered; in other words, it should not stand as a universal or global marker of merit. It should stand for what it really is, that is, a White-Western-serving institution, whose very purpose is extending its power as a brand. Films education needs to deconstruct Oscar’s myth of merit. Oscar is not going to change, but we can stop giving it the power that it will always abuse.

Postscript

abused for calling attention to how Indigenous people are treated in

Hollywood and the United States.

Refusing the Oscars involves risk, evident in the Academy’s recent apology to Sacheen Littlefeather for how she was treated at the 1973 Oscar ceremony when she read a statement on behalf of Marlon Brando, who boycotted the ceremony and refused an acting award due to racist treatment of “American Indians” by Hollywood and the United States.[134] As the current Academy president admits, she was “professionally boycotted, personally harassed and attacked.”[135] The letter characterizes the intimidation and retribution as “abuse.”[136] Hollywood did not treat Brando as it treated as Littlefeather.

Appendix

Since this article’s publication, The Washington Post promoted a list of 25 “most-assigned films” on 4.5 million university syllabi for classes in any field, taught between 2015 and 2021.[137] Spike Lee was correct. His Do the Right Thing is number 2, and Driving Miss Daisy did not make the list. Lee is also one of two not-White directors. The other is the only not-Western: Kurosawa Akira for Rashoman (Japan, 1950), so no not-Western films produced in our lifetimes makes the list. Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (USSR, 1929) is number 1. There are only two films directed by women, both White. At number 20 is Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris Is Burning (USA, 1990) on Blank and Latinx gay and transgender ball culture, which is also the only film to consider LBGTQ+ people. Leni Riefenstahl’s The Trump of the Will (Germany, 1935), a celebration of Adolf Hitler, is number 8, just below D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (USA, 1915), a celebration of the Ku Klux Klan. In his introductory textbook, first published in 1999 before most undergraduate students were born, Robert Kolker describes Riefenstahl and Griffith as “unredeemable figure in film history.”[138] The presence of their most racist films on this list is troubling since faculty today generally do not subject students to overtly racist films in their entirety but instead opt to screen films that respond to them by deconstructing their racism. In all 21 of 25 films are directed by White men. Not surprisingly, Lee’s film is the only one on the list that addresses racism since the onus of calling attention to oppression typically falls on those who suffer from oppression.

The data is compiled by the Open Syllabus, which indicates that 75% of the syllabi are from universities in White-majority Western states (i.e., Australia, Britain, Canada, and the United States).[139] Searching states with the world’s largest industries based on the number produced annually, the list reveals only eight films (six of which are Bombay or Bollywood films) from the world’s largest, India; zero from the second largest, Nigeria; three from the third largest, China; 30 from the fourth largest producer, Japan; plenty from the fifth largest, the United States; only four (all from the past two decades) from the sixth largest, South Korea; and about 143 from the seventh largest, France. Leaving aside the implicit disempowerments of limiting film education to feature-length narrative films—Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien andalou (France, 1929) is the only short film to make the top 25, the unrepenting eurocentrism of these syllabi is out of step with reality. There are only seven films from México; six from Brazil; five from Taiwan; four from Argentina; three each from Iran (all by Abbas Kiarostami), Sénégal, and Turkey, one each from Colombia, Israel, and Thailand; and zero from Algeria, Cameroon, Ghana, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Lebanon, Kenya, Morocco, Pakistan, Philippines, South Africa, Syria, Tanzania, or Uganda. The data shows that film educators practice erasure more than the tokenism that administrators request. How are students going to be prepared for the present, much less the future, when they are likely watching three films by Alfred Hitchcock and none from a not-White or not-Western woman?

Originally published in Jump Cut, volume 61 [link]

Notes

[1] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Perennial, 1980). James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Book Got Wrong (New York: The New Press, 1995).

[2] Critical race theory (CRT) examines how law defines race. U.S. politicians exploit “white fragility” (i.e., discomfort when Whites talk about race and racism) and foment “white rage” (i.e., violence from discomfort) by claiming that CRT is taught in primary or secondary schools to make White children feel bad about themselves. Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016). Robin DiAngelo, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (Boston: Beacon Press, 2020).

[3] Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, “Rhodes Must Fall,” Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization, ed. Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (New York: Routledge, 2018), 222–242. University students across South Africa pronounced, “Rhodes Must Fall,” because Cecil Rhodes symbolized the hegemonic willingness to overlook systemic racism.

[4] I use the terms not-White and not-Western rather than non-White and non-Western. My initial impulse was to use more-than-White and more-than-Western to emphasize exceeding the limits of Whiteness and Westernness, rather than failing to meet the threshold of Whiteness and Westernness—and also to use White-only and Western-only to emphasize lack.

[5] Decolonization begins with manifestos by Third Worldist filmmakers cited below. Also see: Teshome Gabiel’s Third Cinema in the Third World: The Aesthetics of Liberation (Ann Arbor: UMI Research, 1982). Roy Armes, Third World Film Making and the West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987). Jim Pines and Paul Willemen, Questions of Third Cinema (London: British Film Institute, 1990).

[6] Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (New York: Routledge, 1994/2014).

[7] Usha Iyer, “A Pedagogy of Reparations,” Feminist Media Studies 18, no. 1 (2022), 181, 186.

[8] Bethany Lacina and Ryan Hecker, “The Academy Awards Will Have New Diversity Rules to Qualify for an Oscar. But There’s a Huge Loophole,” Washington Post (23 April 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/04/23/academy-awards-will-have-new-diversity-rules-qualify-an-oscar-theres-huge-loophole/.Kyle Buchanan, “The Oscars’ New Diversity Rules Are Sweeping but Safe,” New York Times (16 May 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/09/movies/oscars-best-picture-diversity.html. To illustrate the article, a photo of a White woman spraying gold paint on a larger-than-life statue of the Oscar statuette is captioned: “The Oscars, like this statue, need their luster restored.”

[9] The Immigration Act of 1965 eliminated the “national quotas” on immigration, which were associated with preventing European Jews from escaping death under the Nazis but also worked to minimize immigration from not-White/not-Western states. Affirmative Action employs quotas that disproportionately favor White women.

[10] Maggie Hennefeld, “The Work of Art in the Age of Flexible Inclusion Criteria,” Film Quarterly (30 September 2020), https://filmquarterly.org/2020/09/30/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-flexible-inclusion-criteria/.

[11] Hennefeld, “The Work of Art.”

[12] Hennefeld, “The Work of Art.”

[13] Elaine Teng, “Michael Caine on #OscarsSoWhite: Black actors Should ‘Be Patient’,” The New Republic (22 January 2016), https://newrepublic.com/article/128207/michael-caine-oscarssowhite-black-actors-be-patient.

[14] Rachel Donadio, “Charlotte Rampling Says Oscars ‘Boycott’ Is ‘Racist Against Whites’,” New York Times, (22 January 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/23/movies/charlotte-rampling-says-oscars-furor-is-racist-against-whites.html.

[15] Jessica Valent, “Abuse Isn’t Romantic. So Why the Panic That Feminists Are Killing Eros?,” The Guardian (12 January 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jan/12/abuse-isnt-romantic-feminists-eros-me-too.

[16] Eugene Franklin Wong, On Visual Media Racism: Asians in American Motion Pictures (New York: Arno, 1978).

[17] Nancy Wang Yuen, Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2017).

[18] Latonja Sinckler, “And the Oscar Goes to; Well, It Can’t Be You, Can It: A Look at Race-Based Casting and How It Legalizes Racism, Despite Title VII Laws,” Journal of Gender, Social Policy & The Law 22, no. 4 (2014), 861.

[19] Sharon Willis, High Contrast: Race and Gender in Contemporary Hollywood Film (Durham: Duke University, 1997).

[20] Sinckler, “Oscar Goes to,” 875.

[21] Derek Thompson, “Oscar Voters: 94% White, 76% Men, and an Average of 63 Years Old,” The Atlantic (03 March 2014), https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/03/oscar-voters-94-white-76-men-and-an-average-of-63-years-old/284163/.

[22] Olúfémi O. Táíwò, Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everythig Else) (Chicago: Haymarket, 2022), 4–5.

[23] In What’s the Use?, Ahmed describes how University College London erased the term eugenics to whitewash the name Francis Galton (166–167). Rhodes was racist, but scholarships named after him are granted to racially/ethnically “diverse” students.

[24] The Brian Lehrer Show, “Wendell Pierce on #OscarsSoWhite,” WNYC (22 January 2016), https://www.wnyc.org/story/wendell-pierce-oscarssowhite/.

[25] As cited in Clayton Davis, “Latinos’ Absence in Hollywood Has Felt Deliberate. Is 2021 the Year It Changes?,” Variety (08 April 2021), https://variety.com/2021/film/awards/latino-movies-in-2021-hollywood-oscars-representation-1234946882/.

[26] As told to Scott Feinberg, “Brutally Honest Oscar Ballot #2: Get Out Filmmakers ‘Played the Race Card’, ‘Just Sick of” Meryl Streep’,” Hollywood Reporter (02 March 2018), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/lists/brutally-honest-oscar-ballot-get-filmmakers-played-race-card-just-sick-meryl-streep-1090440.

[27] Madhusree Mukerjee, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II (New York: Basic Books, 2011).

[28] Esther Breger, “The ‘Hollywood Blackout’ at the 1996 Academy Awards,” The New Republic (29 January 2016, https://newrepublic.com/article/128584/hollywood-blackout-1996-academy-awards.

[29] Jacqueline Keeler, “‘#OscarsSoWhite, Again: A Symptom of Hollywood’s Racism” New America Media (16 January 2016), http://newamericamedia.org/2016/01/oscarssowhite-again-a-symptom-of-hollywoods-racism.php.

[30] Keeler, “‘#OscarsSoWhite, Again.”

[31] Deborah Shaw, The Three Amigos: The Transnational Filmmaking of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), 1–2.

[32] Jorge Cotte, “Are Roma’s Oscar Nominations a Win for Diversity or a Different Shade of Whiteness in Hollywood?,” Remezcla (15 February 2019), http://remezcla.com/features/film/alfonso-cuaron-oscar-nomination-diversity/.

[33] Yasmina Price, “Western Films About Africa Are Neocolonial Even When They Try Not to Be,” Hyperallergic (30 May 2021), https://hyperallergic.com/648474/stop-filming-us-congo-documentary-colonialism/.

[34] Lee’s Sense and Sensibility (USA/UK, 1998) was recognized at BAFTA.

[35] John Tomlinson, Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction (London: Continuum, 1991), 54.

[36] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (Woodbridge: James Currey, 1986), 3.

[37] Ngũgĩ, Decolonising the Mind, 3.

[38] Cited in Ngũgĩ, Decolonising the Mind, 29.

[39] Stella Kim and Hanna Park, “Youn Yuh-jung is Just Not That into Hollywood,” NBC News (28 April 2021), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/k-grandma-youn-yuh-jung-just-not-hollywood-n1265530.

[40] Producers want to make money across markets, and Parasite’s producer Kwak Sin-ae is CEO of a major media company.

[41] Brian Hu, “Commentary: Parasite Became an Oscars Success Story Overnight Because of Years of Asian American Support,” The San Diego Union-Tribune (13 February 2020), https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/opinion/story/2020-02-13/parasite-oscar-bong-joon-ho-best-picture.

[42] Henry Aray, “Oscar Awards and Foreign Language Film Production: Evidence for a Panel of Countries,” Journal of Cultural Economics (2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-020-09402-3.

[43] Aray, “Oscar Awards and Foreign Language Film Production.”

[44] Unifrance, “24 French Coproductions in the Running for the Oscar for Best International Feature,” Unifrance (05 November 2021), https://en.unifrance.org/news/16165/24-french-coproductions-in-the-running-for-the-oscar-for-best-international-feature.

[45] Paul McDonald, “Miramax, Life is Beautiful, and the Indiewoodization of the Foreign-language Film Market in the USA,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 7, no. 4 (2009), 357, 358.

[46] Karina Longworth, “The Legend of Harvey Scissorhands,” Grantland (15 October 2013), https://grantland.com/features/does-harvey-weinstein-help-hurt-movies/.

[47] Robert Stam and Ella Habiba Shohat, “Film Theory and Spectatorship in the Age of ‘Posts’,” in Reinventing Film Studies, ed. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams (London: Arnold, 2000), 382.

[48] Swapnil Dhruv Bose, “Martin Scorsese Named His 125 Favourite Films of All Time,” Far Out (12 December 2021), https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/martin-scorsese-125-favourite-films-of-all-time.

[49] Anna Cooper, “A New Feminist Critique of Film Canon: Moving Beyond the Diversity/Inclusion Paradigm in the Digital Era,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 36, no. 5 (2019), 392–413.

[50] Gomery, Hollywood Studio System, 181; Philip H. Gordon and Sophie Meunier, “Globalization and French Cultural Identity,” French Politics, Culture & Society 19, no. 1 (2001), 22–41.

[51] Ruth Vasey, “The World-Wide Spread of Cinema,” in The Oxford History of World Cinema, ed. Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 53.

[52] Gomery, Hollywood Studio System, 65.

[53] Toby Miller, “Hollywood and the World” in The Oxford Guide to Film Studies, ed. John Hill, Pamela Church Gibson (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 373.

[54] Terms like Bollywood (Mumbai), Chinawood (Dongyang), Hallyuwood (Seoul), Lollywood (Lahore), Kollywood (Chennai), Mollywood (Kerala, mostly Kochi), Nollywood (Nigeria, especially Lagos), and Tollywood (Hyderabad) are also problematic.

[55] Julio García Espinosa, “For an Imperfect Cinema” (1969), trans. Julianne Burton, Jump Cut 20 (1979), https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC20folder/ImperfectCinema.html.

[56] Satyajit Ray, “What’s Wrong with Indian Films?” (1948), Our Films, Their Films (Bombay: Oriental Blackswan, 1976), 22.

[57] Chandak Sengoopta, “‘The Universal Film for All of Us, Everywhere in the World’: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and the Shadow of Robert Flaherty,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 29, no. 3 (2009), 278, 280.

[58] Mahen Bonetti and Carlos A. Gutiérrez, South of the Other (New York: The Flaherty/International Film Seminars, 2007).

[59] Douglas Gomery, The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2005), 68; Emanuel Levy, All about Oscar: The History and Politics of the Academy Awards (New York: Continuum, 2003), 41.

[60] Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin, America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies (Malden: Blackwell, 2004), 31.

[61] Toby Miller, Nitin Govil, John McMurria, and Richard Maxwell, Global Hollywood 2 (London: British Film Institute, 2005).

[62] Ijeoma Oluo, Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male Power (London: Basic Books, 2020), 6.

[63] Oluo, Mediocre, 6.

[64] Sarah Ahmed, What’s the Use?: On the Uses of Use (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 194.

[65] Mary McNamara, “It’s Time for Hollywood to Stop Defining Great Drama as White Men Battling Adversity,” Los Angeles Times (15 January 2016), http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/envelope/la-et-st-oscars-mcnamara-notebook-white-hollywood-20160115-column.html.

[66] Matthew W. Hughey, The White-savior Film: Content, Critics, and Consumption (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014), 8.

[67] Cited in Marlow Stern. “Spike Lee Blasts ‘Selma’ Oscar Snubs: ‘You Know What? F*ck ’Em’,” Daily Beast (12 July 2017), https://www.thedailybeast.com/spike-lee-blasts-selma-oscar-snubs-you-know-what-fck-em?ref=scroll.

[68] They are 20 Feet from Stardom (USA, 2013; dir. Morgan Neville) and The White Helmets (UK, 2016; dir. Orlando von Einsiedel), in which White-Western filmmakers tell not-White or not-Western stories, and O.J.: Made in America (USA, 2016; dir. Ezra Edelman) on O.J. Simpson and perhaps also Searching for Sugar Man (Sweden/UK/Finland, 2012; dir. Malik Bendjelloul) about two White South Africans, saving Native American singer Sixto Rodriguez from obscurity.

[69] Caty Borum Chattoo, “Oscars So White: Gender, Racial, and Ethnic Diversity and Social Issues in U.S. Documentary Films (2008–2017),” Mass Communication and Society 21 (2018), 380.

[70] Short documentaries include Saving Face (USA/Pakistan, 2012; dir. Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy and Daniel Junge), A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness (USA/Pakistan, 2015; dir. Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy), and Period. End of Sentence (USA, 2018; dir. Rayka Zehtabchi). The only winner to focus on positive events outside United States is Strangers No More (Israel, 2010; dir. Karen Goodman and Kirk Simon) on an Israeli school attended by immigrant children.

[71] Purnima Bose, Intervention Narratives: Afghanistan, the United States, and the Global War on Terror (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 9–11.

[72] Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow, “Introduction: Beyond Story,” World Records 5, no. 1 (2021), 9.

[73] “The current socio-historical context has transformed storytelling into an unchallenged neoliberal palliative, a way to make us feel better, a means of preventing us for attending to necessary paradigm shifts.” Lebow and Juhasz, “Beyond Story,” 9.

[74] Occasionally, films somewhat critical of U.S. policy win, including The Panama Deception (USA/UK, 1992; dir. Barbara Trent) and Taxi to the Dark Side (USA, 2007; dir. Alex Gibney).

[75] Lila Abu-Lughod, “Do Muslim Women Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others,” American Anthropologist 104, no. 3 (2002), 787; Charles Hirschkind and Saba Mahmood, “Feminism, the Taliban, and the Politics of Counter-Insurgency,” Anthropological Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2002), 107–122.