Milestones and Arrows: A Cultural Anthropologist Discovers the Global African Diaspora

The United Nations (UN) declared 2015–2024 the International Decade for People of African Descent with the guiding themes of Recognition, Justice, and Development. Recognition, the theme here, which might be considered foundational to the others, refers to “the contributions of the African continent and of people of African descent to the development, diversity and richness of world civ- ilizations and cultures, which constitute the common heritage of humankind.”¹ This beginning of the UN Decade, which corresponds to the centennial year of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History and The Journal of African American History, is an ideal moment to reflect on the worldwide presence of people of African descent. As a cultural anthropologist who has been journeying on the paths of the global African Diaspora for decades, I will seek to recreate high points of my itineraries of discovery. Milestone events resulted in increased knowledge and new perspectives, and a map of arrows kept me focused on getting to places of diasporic revelations.

“Welcome Home” To Africa

I began to learn about the global African Diaspora, the worldwide presence of peoples and cultures of African origin, in Cameroon in Central Africa on my first trip outside the United States when I was nineteen. As a result, Africa and an evolving concept of a global African Diaspora have been an integral part of most of my life. I could not have gone to Africa at a better moment in history or in my life. Nor could I have had a better introduction to the continent than by spending a summer in the vibrant and diverse country that characterizes itself as “Africa in Miniature.” Plus, I was privileged to live with a family that was proud of their rich culture and treated me like a daughter and sister.

In defiance of entrenched stereotypes of Africa, the Bamum people who welcomed me to their capital of Foumban had a royal dynasty dating back centuries, and a rich artistic tradition represented in major international museums. Their legendary King Njoya (whose reign was 1895-1923) had built a three-story palace in the early 1900s which the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) helped to restore in the 1990s. The king had also invented a writing system for the Bamum language in which he had written several books that were used in the schools he created. His most significant work was Histoire et Coutumes des Bamum/History and Customs of the Bamum.²

Alex Haley had not yet written Roots (1976), which inspired many African Americans to become interested in our African heritage and think we could, and should, want to know it. That was more than ten years off. So, I can’t claim to have been seeking an ancestral heritage in Cameroon. What I was seeking were adventures to broaden my adolescent world. I had been anxious to experience other cultures since childhood visits to an aunt living in Manhattan’s Chinatown exposed me to people who looked different and spoke and wrote differently from everyone I knew. They made me think that there was much to see out in the world.

So, when my Cameroonian host family welcomed me “to the source,” I didn’t understand what they meant.

“You are a black American, aren’t you?” they asked. “Of course.”

The transition from “Negro” to “black” was recent. “Then your ancestors came from Africa, right?”

“I guess so.”

We weren’t yet “Afro-American” and were two decades from becoming “African American.”

“So, welcome to the source. Welcome home.”

By the end of my stay with my Bamum family I really felt at home, and I have returned to Foumban again and again.

My Cameroonian “parents,” with no post-secondary education but an enlightened Pan-Africanist consciousness, also surprised me with their knowledge of African American culture. Their knowledge contrasted starkly with my ignorance about their African culture. They asked about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, and compared it with African independence movements. It was 1964, the year the Civil Rights Act presumably made African Americans full citizens of the United States. And Cameroon had become formally independent of European colonization in 1960. So, it was a period of great optimism for us on both sides of the Atlantic.

My Cameroonian family asked if I knew Olympic sprinter Wilma Rudolph, whom they affectionately called the Black Gazelle. I did. They also asked if I knew Brazil’s soccer king, Pele. I didn’t. They were as proud of these people from the other side of the Atlantic as we were proud of accomplished African Americans. That was my first inkling that these Africans had a sense of international connections that I did not yet understand. I knew next to nothing about Brazil and had no idea that Afro-Brazilians constituted the majority of Brazil’s population, or that they were second only to Nigeria in population of African origin.³

After asking me if I had brought them records of the African American music they enjoyed (I was too embarrassed to admit that I had not thought they would know our music much less have electricity or record players), they played music by Harry Belafonte, Ray Charles, and Mahalia Jackson. At parties we danced to Caribbean music from Cuba, Trinidad, and Guadeloupe, and to Nigerian and Ghanaian High Life, all of which the Cameroonians characterized as “their music.”

The family was surprised and pleased that I knew how to dance to these varied African Diasporan and African musics. I told them that we danced to Caribbean and Latin music in New Jersey and that I knew the High Life from college parties with African students. But I didn’t yet understand the commonalities between these musics that led my African hosts to characterize them as theirs. I didn’t know that concepts of what constituted music and how to make and move to it had traveled to the Americas in the heads of Africans enslaved by Europeans and Euro-Americans to do the work of building the Americas.⁴

Although brought to be worked to death to develop a new world, and in most places either prohibited from making music and dancing or constrained to do so in ways not of their choosing, Africans and their descendants throughout the Americas nevertheless continued to make music based on African concepts and to dance to survive by maintaining links with divine forces and for essential recreation. These music and dance forms were modified by the encounters in the Americas, yet retained enough of their original identities that when they returned to their continent of origin, Africans still recognized them as theirs.⁵

Probably without even knowing they were doing so, my Cameroonian family was making me aware of the African origins of African American culture and of the existence of a larger web of continuities and connections from Africa to the Americas and among African Diasporan societies. They were laying the foundation of my African Diasporan consciousness, educating me into their international sense of Africanity based on their recognition of links between Africans and Africans in the Diaspora. This was decades before most of us in the United States had begun thinking about ourselves within the concept of “the African Diaspora.”⁶ Some of these connections were evident in the most basic elements of daily life, such as food. Bamum dishes that I initially considered unpleasantly strange ceased to seem strange as I began to not only love them, but to appreciate their similarities to African American foods. White balls of corn meal fufu began to seem like ancestors of our white corn meal grits. The delicious greens we ate most days—njapshe, shem, and others—recalled the greens—collards, kale, mustards, turnips—that I loved at home. Bamum dishes have now augmented and enhanced my concept of “Soul food.”⁷

My Chinatown experiences had inspired me to want to travel and get to know other peoples and cultures in the world. I was majoring in political science to prepare for a diplomatic career—the only people I had encountered whose careers involved international travel being African diplomats. My Cameroonian family changed my career aspirations by inviting a French anthropologist to lunch. Claude Tardits was doing research about the Bamum Kingdom that resulted in the monograph, Le Royaume Bamoum/The Bamum Kingdom.⁸ He talked about his experiences living with and learning from the Bamum and about anthropology’s participant-observer research methodology.

I was immensely enjoying what I later realized was my proto-anthropological experience of learning about Bamum culture by living with Bamum people, observing while participating, and asking lots of questions. So in Foumban, in addition to beginning to learn about my own African heritage and about the global African Diaspora, I also realized that I could make a career of experiencing the world as a cultural anthropologist.

Decades later I was invited to the 2013 “International Colloquium on King Njoya” at Cameroon’s University of Yaoundé. The inevitable theme of my talk and article for Le Roi Njoya: Créateur de Civilisation et Précurseur de la Renaissance Africaine/King Njoya: Creator of Civilization and Precursor of the African Renaissance, was how the society King Njoya had been so significant in molding had led this African American to research the global African Diaspora.⁹

Finding “The Spirit”

My Cameroon experiences led me to do graduate work in cultural anthropology. My master’s thesis at the University of Chicago was about the phenomenon of spiritual trance that had intrigued me since, at age eight, I first saw well-dressed ladies in fancy hats “get happy,” and be “filled with the Spirit,” at a Baptist church in Newark, New Jersey. This was my first vision of the Africanity of African American culture. Of course, I didn’t know that at the time. Nor, I’m quite sure, did others in the church, including the ladies in question. Intrigued by this expres sion of a spiritual experience, I wanted to know more about this “Spirit.” What was its name, where did it come from, and especially why did it act as it did?

For my thesis, published as Ceremonial Spirit Possession in Africa and Afro- America, I read extensively about African derived spiritual systems in Brazil: Candomblé; Cuba: Yoruba/Lucumi/Ocha/Santeria; Suriname: Winti; and Haiti: Vodou.¹⁰ They gave me a context for understanding the behavior reflecting the intimate relationship between the human and the divine that I had observed in the New Jersey church. It was my Cameroon experiences that had made me assume that I could better understand African American behaviors within the comparative context of a larger African Diasporan perspective that included African origins.

I attended my first Candomblé ceremony on my first Brazil trip to Salvador da Bahia in 1976. Gestures of people who “incorporated” and danced for Orishas, the spiritual beings of the West African Yoruba people taken to Brazil, reminded me of the ladies “filled” with the Spirit in the Newark church. The Orishas represent forces of nature and human life. They have personalities, stories, colors, and favorite foods. Their dance gestures reflect their roles in the cosmos. Oshun’s area of nature is fresh water; she represents wealth and femininity, her color is yellow, and she dances looking vainly at herself in a mirror. Maternal Yemanja’s area of nature is the ocean, and she is the protector of fishermen. Her colors are blue and white, and her dances represent the moods of the sea, from calm to turbulent.

Decades later and on the other side of the Atlantic, in Morocco in North Africa in 1998, I saw on the front page of a local newspaper that there would be a Gnawa festival and symposium in the town of Essaouira. A review of a recently published book said that the author compared Gnawa spiritual practices, which included sacred trances, to Brazilian Candomblé, Cuban Yoruba, and Haitian Vodou.¹¹ I obviously had to find my way to Essaouira, and arrived just in time to talk my way into a Gnawa ceremony.

The Gnawa are descendants of Sub-Saharan Africans who were enslaved and brought across the Sahara Desert to Morocco. In a song some Gnawa refer to themselves as Ouled Bambara, children of the Bambara, a major ethnic group in Mali. Ceremonies allow their spiritual beings, the Mlouk, to come into the human community in the entranced bodies of their devotees when summoned by the rhythms of the guenbri, a three-string lute. Mimoun, in black, symbolically opens the ritual door so that other Mlouk can enter. Dressed in blue, Sidi Moussa, patron of sailors, dances with swimming gestures. And yellow-clad Lala Mira, who likes sweets and perfume, dances coquettishly.¹²

I went to a bookstore the next day to purchase the book I had read about and found the author, Abdelhafid Chlyeh, present. When I introduced myself, he said that another Sheila Walker had written a book about the topic. He showed me the bibliography and pointed to the reference—my Ceremonial Spirit Possession.

Abdelhafid invited me to the next symposium where my presentation was about similarities, I could not help noticing between the Gnawa Mlouk and Afro-Brazilian Orishas. Eshu is the Orisha who, like Mimoun, opens the way so that the other Orishas can enter ceremonies, and his colors are black and red. Although their genders are different, the similarity between Sidi Moussa and Yemanja is apparent, as is that between Lala Mira and Oshun. These similarities were especially striking because not only were the African origins different—Bambara from Mali as opposed to Yoruba from Nigeria and Benin—but the contexts were also different—a North African Muslim society as opposed to a South American Christian one. My publication from the symposium was Les divinités africaines dansent aux Amériques et au Maroc/African Divinities Dance in the Americas and in Morocco.¹³

Discovering Diaspora Anthropology

While at the University of Chicago I discovered the writings, based on her field research, of Zora Neale Hurston. Best known for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, Hurston’s anthropological works were Mules and Men: Negro Folktales and Voodoo Practices in the South and Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica.¹⁴

I also discovered that dancer Katherine Dunham, internationally known for her pioneering Katherine Dunham Company, had studied anthropology at the University of Chicago decades earlier. She had done field research in Jamaica, Haiti, and Martinique and had used in her performances movements learned in those cultures. The full body undulation characteristic of the Dunham barre is based on the movement of the lwa, Dambala in Haitian Vodou. And L’Agya, the title of one of her well-known dances, recalls the martial art form of that name from Martinique. Her books Journey to Accompong (1946) and Island Possessed (1969) describe her field research experiences in Jamaica and Haiti that allowed her to make African Diasporan sacred and secular traditions into internationally acclaimed art forms.¹⁵ So I had foremothers as role models in the anthropological study of the African Diaspora, both of whom were known for creative expressions inspired by their field research.

I was also pleased to discover Melville Herskovits’s The Myth of the Negro Past, which drew the same conclusions to which my experiences in Cameroon had led me.¹⁶ The myth Herskovits was challenging was that U.S. African Americans, in contrast with African descendants elsewhere in the Americas whose obvious Africanity was undeniable, had retained no significant African culture. His perspective was based on field research in Dahomey, now Benin, in West Africa, as well as in Brazil, Trinidad, Suriname, and Haiti in the Americas. Comparing phenomena between these societies, and with U.S. African Americans, made visible the continuities and commonalities that characterize the Africanity of the latter. My best example was the African American trance behavior that I understood better after attending the Afro-Brazilian ceremony in which the Orishas came from Africa with names and other characteristics, and their danced gestures reflected their roles in the cosmos.

At the University of Chicago, my doctoral field research in 1971–1972 was on the Harrist Church, an African “separatist” church in Côte d’Ivoire.¹⁷ Again inspired by my Cameroon experience, I perceived similarities between such African churches and African American “separatist” churches like the African Methodist Episcopal Church that separated from the segregationist white church to be autonomous in its worship.¹⁸

In the early 20th century, Christian missionaries whose goal was to “civilize the natives” were an integral part of the European colonization of Africa. Africans already had their own civilized concepts of spirituality and many created new institutions based on elements they found useful in what the missionaries tried to impose, while rejecting those they did not. Now all over the continent there are churches that reflect African ways of being Christian.¹⁹

While doing field research in Côte d’Ivoire, I also traveled through much of West, Central, and East Africa, absorbing cultural knowledge that has made Africa an integral part of my worldview. More than seventy trips to about forty countries on the world’s most diverse continent have given me a foundation for recognizing African elements in African Diasporan cultures and interpreting connections among them.

Beginning Milestones and A Map with Arrows

After my experiences in Cameroon laid the foundation, the first milestone on my path to knowing the global African Diaspora was my participation in the “First Congress of Black Culture in the Americas.” It was organized in 1977 in Cali, Colombia, by Afro-Colombian anthropologist and writer Manuel Zapata Olivella and Afro-Brazilian artist, writer, and political leader Abdias do Nascimento.²⁰

Participants were from several African countries and from predictable and unexpected places in the Americas. I learned that there were African Diasporan com munities in more parts of the Americas than I suspected. When at a party I met a man from Ecuador and told him I was surprised to meet an African descendant from a country where I thought there were mainly Indigenous people, his response was, “Dance with me. Then you’ll really know there are Black folks in Ecuador.” A second milestone conference two years later taught me that the African Diaspora extended far beyond the Americas. It was historian Joseph Harris’s 1979 “Global Dimensions of the African Diaspora” conference at Howard University in Washington, DC, which led to the book of the same name.²¹ Harris’s pioneering understanding of the global nature of the African Diaspora stemmed largely from his research in India. His book The African Presence in Asia: Consequences of the East African Slave Trade focused on voluntary as well as involuntary African migrations eastward from the continent. It also highlighted outstanding individuals of African origin and their monumental accomplishments in such unexpected places.²²

I attended many of Harris’s lectures that focused on his 1980 map of these global dimensions, which I was later pleased to find as part of the Rand McNally classroom map collection. Arrows on The African Diaspora map led from places of origin in Africa to places of resettlement across oceans, seas, and deserts. The arrows extended westward from Africa across the Atlantic Ocean to familiar places in the Americas, as well as unfamiliar ones east and north of the continent.²³ I was anxious to follow those arrows leading east and north to places where I would not have expected to find people of African origin.

Fieldwork in Brazil—Largest Nation of The African Diaspora

In 1980 I began ongoing field research in Brazil on the now rather well-known Africanity of the state of Bahia.²⁴ I then broadened my research to areas such as the state of Minas Gerais where expressions of Africanity are very different. In Bahia, the cultures most obviously represented are Yoruba and Ewe-Fon from West Africa, called in Brazil the Nago or Ketu and Jeje “nations,” and the Angola “nation” whose origins are mainly from West Central Africa. The spiritual system known as Candomblé or the Orisha tradition features African spiritual beings that are venerated in ceremonies involving polyrhythmic drumming, costumed dancing, and sacred trance.

Many think that the way Africanity is expressed in the predominantly Yoruba culture of Bahia characterizes Afro-Brazilian culture. But along with having the largest population in the African Diaspora, Brazil, not surprisingly, also has the greatest diversity in its expressions of Africanity. In Minas Gerais and other central-south and southern states, for example, spirituality of African origin is manifest in a form of Afro-Catholicism called Congada or Congado. Its African origins are from what are now the two Congos and Angola in West Central Africa and Mozambique in South East Africa.²⁵ Stories accounting for the origins of Congada speak of interactions between Africans characterized as Congos and Mozambiques who met in Brazil and maintain distinguishing symbols and roles in their ceremonies.

Unlike the veneration of African spiritual beings in Bahia, congadeiros in Minas Gerais seek blessings and guidance from Catholic saints. The spiritual beings of Congada are the Virgin Mary as Our Lady of the Rosary, and Afro- Catholic Saint Benedict, patron of Palermo in Sicily, whose parents were Ethiopian; and Saint Ephigenia from Ethiopia. During ceremonies, which involve Congo queens and kings and royal accoutrements such as capes, crowns, and staffs of office, congadeiros play drums and dance in processions to, around, and inside churches and chapels.

In Belo Horizonte, capital of Minas Gerais, I visited a Congada community that its members called a Mozambique Kingdom. It had a Congo queen, in its chapel were statues of Ethiopian saints Benedict and Ephigenia, and they called their drums goma. Ngoma in much of Bantu-speaking Africa means drum, rhythm, music, dance. I was struck by this everyday Pan-African synergy that the members of the kingdom did not understand as such because, knowing nothing about Africa, they had little idea to what extent they were recreating a Pan-Africa in the Americas.

The Afro-Brazilian Congada reflects a continuity of the royal culture of the Kongo Kingdom that, from 1390 to 1891, dominated West Central Africa from northern Angola in the south to Gabon in the north, which is also the area from which more than 45 percent of Africans were transported to the Americas.²⁶ This African expression takes the form of Afro-Catholicism in Brazil because a characteristic of the Kongo Kingdom was that with the arrival of the Portuguese at the end of the 15th century, its kings and elites converted to Catholicism, and it became known as a Christian kingdom. Thus, in parts of Brazil, Africans recreated an African Christian kingdom that their descendants continue to re-enact.

Panama Congos and Mapping “New Africa”

The other place in the Americas where Congo royal pageantry continues to thrive is Panama in Central America, where I have been doing fieldwork since 2003 during the annual Congo Period, 20 January to Ash Wednesday. Groups of people who identify as Congos in villages and towns along the Caribbean coast, and people from that area living in Panama City, speak “Congo” and build “palaces” of natural materials in which, led by their queens and kings, they drum, sing, and dance Congo on weekends and during carnival.²⁷ Whereas in Brazil it is clear that Congada is about African origins, even if participants know little about their African history, the interpretation that I have too frequently heard in Panama is that the Congos’ royal behavior represents “a parody of the Spanish crown,” rather than continuity with an African royal tradition. No one has had an answer when I have questioned when and how enslaved Africans and Afrodescendants in Panama had contact with the Spanish crown so as to know how to parody it. A less Eurocentric interpretation is that the phenomenon called “Congo” in Panama represents a recreation of the West Central African Kongo Kingdom. That Panama’s Congo phenomenon echoes that of Brazil buttresses that interpretation.

Panama’s Africanity is also explicitly written into its toponymy. Many places have names that trace an African map of the country such as La Guinea: Guinea historically designated West Africa and sometimes Africa in general; Mandinga: the major ethnic group of the Mali Empire; Carabali Hill, Calabar: an ocean port area in eastern Nigeria through which many people traveled on their way to the Americas; and El Congo, plus at least four Congo Rivers: the Kongo Kingdom. Interestingly, Panamanians, including both people who live in places with such names and Afro-Panamanians presumably interested in their African heritage, seem totally unaware of the existence and significance of what one might call a map of Nueva Africa/New Africa.

South America’s Southern Cone

In 1991, I participated in a conference organized in Buenos Aires by a religious institution of middle-class white Argentinian devotees of the Yoruba Orishas, an influence that had come from Brazil. Although mildly curious about the phenomenon of whites adopting African spiritual traditions, my real motive for attending was in hopes of meeting African descendants from the region, despite having been informed that they did not exist. Encyclopedia Britannica says that whereas in 1810 Africans and African descendants constituted about 10 percent of Argentina’s population, “the blacks and mulattos disappeared, apparently also absorbed into the dominant population.”²⁸

At the inaugural reception I asked one of the organizers if any Afro-Argentinians might be present. “There’s one,” he said, pointing to the other face in the room that looked like mine. I went over and greeted her.

“Existes?” I asked. “Existo,” she responded.

Meeting Lucia Molina, who not only existed, but was president of the Casa de la Cultura Indo-Afro-Americana in the city of Santa Fe, was exactly what I had hoped for. It was also the beginning of my meeting other African descendants from South America’s Southern Cone: Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Southern Brazil. I met Afro-Uruguayans from Organizaciones Mundo Afro that in the 1990s played a leadership role in helping other Afro-Latin American communities organize themselves.²⁹ That was a high point of consciousness raising and the forging of international connections and collaborations in Afro-Latin America. Mundo Afro held a 1994 conference that brought together Afrodescendants from throughout the Americas, and followed it with several Institutos Superiores de Formación Afro/Advanced Institutes of Afro-Training, in which I participated, with the goal of bringing together Afrodescendant leaders and future leaders to share their knowledge and develop strategies for future action.

The African Diaspora and The Modern World

In 1996, as Director of the Center for African and African American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, I organized, with the support of UNESCO, a conference on “The African Diaspora and the Modern World.” Obviously a milestone for me, it brought together more than sixty people from more than twenty countries in Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

I like to think that this conference was significant in that, in addition to major scholars, I also invited Afro-South American community leaders who had not had the privilege of being able to become researchers, but who were quite capable of representing their communities. By including members of the Diaspora whose very existence was, and too often remains, unknown and sometimes explicitly denied, the conference promoted efforts of such invisibilized communities to become more visible in their nations and internationally. Such international exposure often led to greater domestic consideration. I was surprised when some of my scholarly colleagues asked me how I had found the Afro-South American participants. “I went to where they live” was my response.

Two results of the conference, both of which included the Afro-South American leaders as well as the scholars, were the edited volume African Roots / American Cultures: Africa in the Creation of the Americas, and the documentary film Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora, which I have recently re-edited and updated.³⁰ When a reporter for The Austin-American Statesman asked where I had gotten the idea to organize a conference on the theme of the roles and accomplishments of Africans and their descendants in creating the modern world, my immediate response was, “Foumban, Cameroon, 1964.” That obviously required an explanation. I told her about my first trip to Africa and how it had put me on the path of getting to know the global African Diaspora. Organizing the conference was part of furthering that process.

From Black to Afrodescendant

On 3 December 2000, my desire to know the major African Diasporan populations of the Americas was satisfied. The Americas Preparatory Conference held in Santiago, Chile, prior to the Durban, South Africa, United Nations World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance, held in August–September of 2001, was a major milestone for the African Diaspora in the Americas and for my knowledge of it.

At the opening ceremony I met the Afro-Chilean delegation from the organization Oro Negro, from the town of Arica in northern Chile. Then I was thrilled to meet a man from Africville, Nova Scotia, at the other extreme of the hemisphere. I visited Africville the following summer to learn about the descendants of the Black Loyalists who were taken there after siding with the British who promised them freedom from their American enslavers during the Revolutionary War, then the War of 1812. The African Methodist Episcopal Church service I attended shouted out its continued links with its African American origins.

Beyond satisfying my desire to know the African Diaspora from Chile to Canada, the Santiago conference also accomplished something much more significant. It brought together, for the first time since our ancestors were deposited throughout the Americas by slave ships, descendants of these scattered Africans— Lusophones, Anglophones, Hispanophones, and Francophones/Creolophones— and we discussed our experiences and preoccupations and found the common ground to write a joint declaration that became a basis for the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action that led to positive public policies for Afrodescendants in some Latin American nations.³¹ It was at Durban that the United Nations declared slavery and the slave trade a crime against humanity, which led to other activities that ultimately culminated in the UN International Decade for People of African Descent.

The statement by Afro-Uruguayan leader Romero Rodriguez, “Entramos como negros y salimos como Afrodescendientes/We came as Blacks and left as Afrodescendants,” sums up well what happened in Santiago. Having arrived as members of African American communities defined by our national identities, we came to recognize our common causes and began to see ourselves in a larger context that transgressed national boundaries and narrow identities to encompass a larger collective and transcending identity as Afrodescendants.

Generating Knowledge from The Inside

In 2002 when I left Texas to teach at Spelman College, I received a United Negro College Fund Global Center grant to develop curricular materials about Afro-Latin Americans. Unable to imagine creating a project about Afro-Latins without their involvement in its conceptualization, I invited Afro-Venezuelan scholar Jesus Chucho Garcia to collaborate with me. Aware that national histories did not tell accurate stories about Afro-Latin populations, especially those whose very existence they denied, we decided to invite Afrodescendant leaders from the nine Spanish-speaking countries in South America to meet in the Barlovento region of Venezuela, where Afro-Venezuelan culture is alive and well. Our goal was to generate a knowledge base for creating valid curricular materials. We came up with key themes for understanding the African Diaspora and asked the invitees to use them to write texts about their communities within the context of their nations’ histories.

In spite of their lack of academic training, the community leaders accepted the challenge of researching and writing about their communities. We had subsequent meetings at Spelman College and, with funds I secured from the InterAmerican Foundation, in Ecuador and Bolivia. During these gatherings we had critical discussions of the texts written by the members of what we called the Grupo Barlovento, and experienced a rich variety of diasporic realities.

I provided feedback on the evolving texts, and under my editorship we completed Conocimiento desde adentro: Los afrosudamericanos hablan de sus pueblos y sus historias/Knowledge from the Inside: Afro-South Americans Speak of their People and their Stories.³² With a chapter on each of the nine countries, the book was initially published in Bolivia in 2010 and republished by Colombia’s Universidad del Cauca in 2013.

In my introduction, I explained how it was that I, an Afro-North American, was editing a book in which Afro-South Americans spoke “from the inside.” I said that as a result of my extensive experiences in most of Africa and the African Diaspora, my sense of identity was as an African Diasporan with a U.S. passport, an accident of the slave ships that had left my ancestors in the United States rather than on other shores. My sense of identification with other African Diasporans around the world is based on our sharing similar historical and contemporary experiences and cultural commonalities. Additionally, given that fewer than 5 percent of Africans were enslaved in the United States compared to more than 45 percent in Brazil, it is statistically improbable for me to be North American rather than South American.

Following Diasporic Arrows East

To begin actively broadening my world beyond the Americas by following Joseph Harris’s arrows, in 2004 I visited a friend who was working in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on the Persian Gulf. On my first evening he introduced me to my first Afro-Emirati. I asked him if any of his ancestors had been pearl divers. His grandfather and father had both been divers. Pearls had been the major source of wealth of the Emirates before oil replaced them, and many divers were Afro-Emirati. I was later surprised to learn that some Africans had been enslaved and brought to the Americas because of their well-known underwater diving skills. They and their descendants dived for pearls in places such as Venezuela’s Margarita Island, Panama’s Pearl Archipelago, and Nicaragua’s Pearl Lagoon.³³

I also asked him if anyone in his family was involved with the Zar, a spiritual system involving trance that I had encountered when working in Somalia and knew existed in Ethiopia and Sudan, areas from which Africans had migrated voluntarily or involuntarily to the Emirates and other Persian Gulf countries. He said that he was a drummer in Zar ceremonies and played for the celebrations of other Emiratis. I was pleased that the two features that I thought characterized Afro- Emirati culture were accurate. It was also clear that this first glimpse of the broader African Diaspora portended by Joseph Harris’s arrows had created an irresistible incentive for me to want to follow more arrows.

Amazingly, while in UAE, as if in immediate fulfillment of my aspiration, I received an email from The African Diaspora in Asia (TADIA) Society inviting me to participate in a conference to be held in Goa, India, in January 2006. I was thrilled about the opportunity to follow another of the arrows on Harris’s map to get to know another aspect of the Diaspora east of Africa, and almost bought a plane ticket for a year too early. I was familiar with much of the limited literature and even a few documentaries on the African Diaspora in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, and was anxious to experience the realities.³⁴

In addition to learning about the research of an international array of scholars, I also encountered the people I most wanted to meet—Afro-Indians or Sidis from the major communities in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and the city of Hyderabad in what is now Telangana state (formerly part of Andra Pradesh). In Gujarat’s capital, Ahmedabad, I visited the Sidi Sayyed Mosque with its delicately carved stone windows, incongruous in the middle of India’s urban traffic bedlam. I also spent time with a Sidi extended family whose courtyard house, and the way people lived in it, reminded me of compounds I had visited in various parts of West and Central Africa.

I was in the village of Ratanpur for the weekly Thursday ceremony for the Sidi saint Bava Gor. Villagers said that Bava Gor had come to Ratanpur from Abyssinia, now Ethiopia, eight hundred years ago as an agate merchant. He revo lutionized the agate stone industry and also demonstrated his spiritual powers by defeating a demoness who had been tormenting the villagers. A devotion to him developed and a shrine that continues to be tended by Sidis was built in his honor. The veneration of Bava Gor has spread beyond the Sidi community and beyond Ratanpur to Mumbai in Maharashtra, as other Indians—Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Zoroastrians—seek healing and blessings from the African saint.³⁵

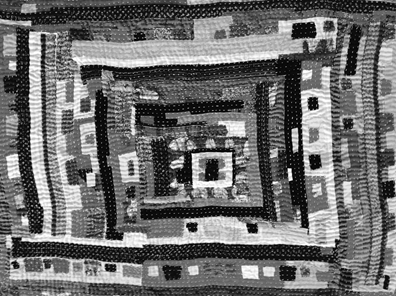

In Maharashtra I took a dhow, an Indian Ocean sail boat, the short distance from the small town of Murud to the unconquerable island fort of Janjira, now a national landmark, from which Sidis had controlled maritime traffic on India’s Konkani coast for centuries.³⁶ And in the southwestern state of Karnataka, I bought from the Sidi Women’s Quilting Cooperative Society a brightly colored kawandi, a patchwork quilt made of sari cloth that is part of the relentlessly diasporic decor of my home.³⁷ Its syncopated aesthetics recall African American quilts.

In 2014, I returned to India to visit the Afro-Indian community in Hyderabad that I had not visited on my earlier trip and to return to Karnataka and Gujarat to learn more about the communities there. In Hyderabad, the African Cavalry Guards’ neighborhood where the Sidi community is concentrated, is located in the middle of the bustling city. Until the creation of the Indian republic in 1947, Sidi men constituted the prestigious African Cavalry Guard of the Nizam or ruler of Hyderabad, wearing fancy uniforms, riding horses, and even playing polo.³⁸

Hyderabad was the most powerful and prosperous of India’s princely states with more than 16 million inhabitants, an airline, a postal service, and other institutions befitting a huge state. With the elimination of the princely state system in 1948, the Sidis lost their role and status and are now part of the urban proletariat. Their drum-based musical style, duff, is popular beyond their community, and musicians I met were about to play for the wedding of a Bollywood star.³⁹

In Karnataka, most Sidis live in small rural communities or in the forest where they harvest and sell products such as honey.⁴⁰ International events had had an impact on them since my previous visit. Members of a honey-selling cooperative showed me photos of the celebration they had organized when Barack Obama was elected president of the United States. A huge poster with a photo of Obama was the backdrop. When I asked why they liked him, they said that he was an “American Sidi.” They also recognized me as one of “their people.”

In an area of Gujarat that I had not visited previously, I had a sense of having experienced the diversity of Sidi realities when I met the Nawab, or ruler of Sachin.⁴¹ Although royalty no longer exists as such, and the Nawab, who is a lawyer, no longer rules over a community, he is an economically privileged high-status person who is still respected for his symbolic role. He took us to visit the family’s two palaces, one functional and the other in ruins.

The Nawab’s Abyssinian ancestors had been palace guards for Mogul emperors who had put a few of these trusted military leaders in charge of the two small princely states of Sachin and Janjira. Because they were small in number and married other elites, these high status Sidis, although acknowledging their African origins, do not have a phenotype reflecting that heritage like the majority of Sidis who have remained as distinct communities.⁴²

An Asian Milestone

By focusing on the African Diaspora in the Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean, South Asia, and other lands east of the African continent, the TADIA conference, which acknowledged the pioneering work of Joseph Harris, broke new ground from the limited perspective of the peri-Atlantic orientation of most African Diasporan research. It made a quantum leap by including a major part of the Diaspora whose existence still comes as a surprise to most.⁴³ It is ironic that the African Diaspora east of the continent is so often missing given that the first documented revolt of thousands of enslaved Africans took place in 9th century Iraq, half a millennium before the formation of the African Diaspora in the Americas.⁴⁴ By adding the long historical and geographically vast experience of this most diverse region of the global African Diaspora, the TADIA conference challenged the hegemony of the Atlantic Diaspora model. It provided new data based on different realities, such as the existence of African elites in India. And it offered new templates for broader and more complex reflections about the global nature of the African Diaspora.

Even more extraordinarily for the kind of undertaking that usually just involves scholars gathered to talk about the people they study, in the absence of and often with little concern for the interests of these people, TADIA conference organizers took the unprecedented step of following it with a workshop for Sidis. They invited a hundred or so Sidis representing communities living far apart in the huge country to meet for the first time. Members of the elite, some of whom had participated in the conference, but who have no particular relationship with the other Sidis, did not attend. Transcending differences in African origins, historical roles in India, language, religion, and regional culture, the Sidis began to get to know each other and to learn what they had in common.

I filmed much of the workshop. It took place in the several languages— Gujarati, Kannada, Urdu, and Hindi—that different groups of Sidis speak, but that I don’t, so I observed visual cues. Initially the Sidis from Gujarat and those who had migrated to Mumbai would dance in their area of the room. Then those from Karnataka would dance on their side. The few individuals from Hyderabad did not seem to constitute a group. Gradually, when one group began to dance, individuals and then small groups from the others would join in. Eventually everyone danced together.

As a result of the TADIA conference and my experiencing several very different Afro-Indian realities, I totally transcended my Atlantico-centricity and became relentlessly global in perspective. My broader worldview is reflected in the documentary Slave Routes: A Global Vision that I produced with a colleague for the UNESCO Slave Route Project. It includes the African Diaspora in Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Persian Gulf—Iraq, Iran, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, India, Mauritius, and the Maldives—as well as in the Atlantic world of Europe and the Americas.⁴⁵

Indian Ocean Maroons

The TADIA conference also allowed me to meet Indian Ocean researchers who further expanded my world by inviting me to conferences and allowing me to learn about the African Diaspora on the Mascarene Islands east of the African continent, especially on Reunion Island. An overseas department of France, similar to Hawaii and Alaska for the United States, Reunion is unique in the African Diaspora in the extent to which the phenomenon of marooning is written into the landscape and toponymy of the island. This is especially true in Les Hauts, the highland heart of the island that was its locus.

Most of the people enslaved on Reunion were from Madagascar and the major inhabited places in the highlands are named for 18th century maroon leaders Salazie, Cilaos, and Mafate.⁴⁶ Salazie and Cilaos are remote rural communities accessible by car on very winding roads. Mafate, which consists of tiny, scattered population clusters, can only be reached on foot or by helicopter. I, of course, had to hike the four hours up the narrow cliff-hugging path to get a feel for the maroon experience.

Mafate, from mahafaty in the Malagasy language, means “lethal.” A tourist brochure said the name referred to the difficult climb. The climb may be the most lethal part of the experience for present day hikers. But Mafate was also the name of a leader of maroons who fled enslavement on lowland plantations to establish autonomous settlements in the volcanic craters of the interior. In the 18th century it was probably the fierce maroon resistance against their would-be re-enslavers that was so lethal.

Like better known maroons in Brazil, Colombia, Jamaica, and Suriname in the Americas, maroons on Reunion Island established their settlements in areas in which they were protected by the topography. Similar to my previous experiences in the maroon communities of the Americas, being in Mafate allowed me to observe immediately the extent to which the terrain itself told much of the story of how the maroons were able to resist capture. Palmares in Brazil is high up a hill surrounded by flatlands. Palenque de San Basilio in Colombia is in a forest and has only been connected for a few decades to a main road by what is still a rutted dirt road that in the rain becomes slippery mud. Accompong in Jamaica, similar to the communities in Reunion, is in the highlands in an inhospitable area characterized by deep ravines where invaders would be visible to those in higher positions. Suriname maroon settlements, accessible only by canoe or footpath, were located above river rapids in the dense rain forest.⁴⁷

Ceremonies for Ancestors East and West of Africa

Reunion also has ceremonies for ancestors from Madagascar and Mozambique. I was pleased to be invited to a servis zancet/service for the ancestors, tellingly in an area of former sugar cane plantations.⁴⁸ And I was thrilled when the family asked me to film them, moving me from the role of tolerated guest film ing them for whatever my purposes might be, to someone trusted by them to film them for their own purposes.

To begin the day, family members sacrificed fowl that an elder female ritual specialist would use to prepare the favorite dishes of the ancestors they expected to come. There would be rice for the Malagasies and tubers for the Mozambicans. During the evening ceremony, immediate ancestors, like the recently deceased husband of our hostess, as well as distant ancestors whose identities had become generic, came to dance in the bodies of people who entered sacred trances to embody them. Individual ancestors were recognized by their familiar dance gestures to their favorite music, and more distant ones by movements and colors identifying their origins.

I wondered if such family-oriented ancestral ceremonies existed on the other side of the African continent in the Americas. I had attended a ceremony for the Yoruba Eguns on Itaparica Island in Bahia, Brazil, one of the few places where such ceremonies exist. But these Eguns were more generic ancestors, not the ancestors of a specific family as on Reunion Island.

The only possibility I could imagine was the Dugu of the Garifuna people of the Caribbean coast of Central America (Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, with origins on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent). I had heard about Dugu ceremonies decades earlier. Whenever I met a Garifuna, I asked him or her to help me attend one. Although they all said they would, no one ever did. Since I was not a member of anyone’s family, no one had a reason to invite me.⁴⁹

Finally in 2012, after doing a workshop about the African Diaspora in La Ceiba, Honduras, for Afrodescendant leaders from Central and South America, I learned that there would be a Dugu in the town of Trujillo, and that the buye, the priestess in charge, had said I could attend. She welcomed me at the door of the dabuyaba, the structure erected for the ceremony, and sprayed me with rum as a purification before escorting me inside. I assumed that I would sit as unobtrusively as possible and watch, but I quickly realized that sitting and watching was not an option. There was no such role. Everyone present danced.

Honored to be in their midst, I danced around and around for three days with two hundred or so red-clad family members who had come together for the occasion. Some had come from the United States to where many Garifuna have migrated. From time to time an ancestor would come into the body of a suddenly entranced descendant to give advice, a message of solidarity, or sometimes a warning to the extended family. Someone asked me if I was shocked. I explained that I had first seen similar trance behavior in a church in New Jersey and then in Candomblé ceremonies in Brazil and a Gnawa ceremony in Morocco, although in those cases the spiritual beings were not ancestors. And I had most recently seen a ceremony for returning ancestors on Reunion Island.

Rather than shocked, I was grateful to be able to observe similar behavior with a somewhat different meaning in this Central American context. Whether the spiritual being was a Christian Spirit in the United States, a Yoruba Orisha in South America, a Gnawa Mlouk in Morocco, a Garifuna ancestor in Central America, or a Malagasy or Mozambican ancestor on Reunion, the principle was about the inti- mate relationship between spiritual and human beings that was manifest in their interaction in ritual contexts.

After three days of dancing for their ancestors, the Garifuna placed enormous offerings of the favorite dishes of their known and unknown ancestors in the ocean for all those who had perished in crossing the waters that had brought them to the shores of Honduras. I was grateful to have participated, on both sides of the African continent, in ceremonies in which ancestors came into the bodies of their entranced descendants to dance, eat, communicate, and promote extended family solidarity.

Pacific America is So African!

Throughout the 21st century I have spent time in Afrodescendant communities in all of Spanish-speaking South America, and have gotten to know where cultures of African origin are the most intensely expressed, such as Ecuador’s Pacific coast. When my plane from the highland capital of Quito descended toward the town of Esmeraldas, my reaction upon seeing the land was “Pacific America is more African than Atlantic America.” The earth and water formations I saw from the air reminded me of landing in Douala in Cameroon, and the vegetation I later saw in rural areas made me think I was somewhere in the West and Central African coastal forest.

Afro-Ecuadorian culture is most concentrated in the province of Esmeraldas, especially in the north in the river communities that I was anxious to visit. In the town of Borbón that is the gateway to the region, I met cultural icon Papa Roncón. He made, played, and taught others to play the marimba, a xylophone-like instrument that exists in many parts of Africa and is emblematic of Afro-Ecuadorian culture. In the Americas the marimba has retained its kimbundu name from Angola. Papa Roncón’s name is Guillermo Ayovi Eraso, Ayovi being a familiar family name in the Esmeraldas as it is along the African coast from Ghana to Cameroon. Afro-Ecuadoreans in the region have retained their African phenotype, and their Spanish has little in common with the one year of college Spanish that gets me by. As a result, I often looked around and wondered exactly where in Africa I was.

In the forest there are few roads to few places. Rivers are the highways, and long motorized canoes are the buses and trucks that transport passengers and merchandise to riverbank villages accessible only by water. I went to the pretty village of Playa de Oro/Beach of Gold on the Santiago River in a canoe that, in addition to twenty or so passengers, was carrying a full-size refrigerator and a giant freezer. Veering at wild angles around huge boulders as we motored up the down-rushing river seemed a little precarious, but we arrived.

In the evening in the light of a kerosene lantern, David Ayovi told me a story about the mermaid living in the river on which I had just traveled. She would sometimes be seen sitting on a rock in the river combing her long hair with a golden comb. If she left the comb on the riverbank and a man took it, he would not be seen again in the village because she would take him to her home at the bottom of the river. I had goose pimples on the hot evening as he was telling the story because I already knew it. I had heard the same story about Mamy Wata, Mother of the Waters, as she is known in Africa, by the Congo River in Central Africa, about which he knew nothing.

In Playa de Oro people still pan for gold. Mina is a common family name because many of their ancestors were brought from what the Portuguese called the Costa da Mina/Coast of Mines or Mina Coast in West Africa. They called the Africans from the area Negros Minas/Mina Blacks, and in the Pacific coast gold- producing areas of Ecuador and Colombia, Mina became a family name. The Mina Coast in West Africa was later called the Gold Coast by the British and is now independent Ghana where Elmina Castle, now a heritage tourism site, was a major point of involuntary departure for enslavement in the Americas.⁵⁰

Beginning in the mid-15th century the Portuguese had engaged in a legitimate gold trade with the Akan-speaking people in West Africa with whose skills and expertise in mining and working gold they were familiar. When the Portuguese and Spanish appropriated the gold mines of the conquered indigenous people of South America, they enslaved African experts, Negros Minas, to mine it. This was one of the major transfers of knowledge and technology from Africa that helped enrich Europe and develop the Americas.⁵¹

In addition to technological expertise, Africans also brought other sources of knowledge to the Americas, such as what might be termed wisdom stories. Afro- Ecuadorean researcher and storyteller Juan Garcia knew both the Br’er Rabbit/Tio Conejo/Uncle Rabbit and the Anansi, the spider cycles of stories common to various parts of the Americas. The former are from West Africa—from Sahelian countries such as Senegal, Mali, and Burkina Faso. The latter are from the Akan-speaking area of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana from which the gold experts came. Garcia used them as they were originally intended—to teach social and cultural values to members of the community.

One day Juan was telling a Br’er Rabbit story to a visitor from Burkina Faso and paused for a drink of water. The Burkinabe man continued the story where Juan left off, finishing it exactly as he would have. Given that Africans have not come to the west coast of South America in centuries, that the stories had remained the same in West Africa and Pacific South America is incredible.

Juan’s Br’er Rabbit story, which was as amazing as my hearing the Mamy Wata story in Playa de Oro, in addition to the family names Mina and Ayovi, plus the marimba, supported my initial observation from the plane about how African the Pacific coast of South America was, and made me know that there was much more to discover. When I have shown my video footage to Africans from various parts of the continent, seeing the environment and people—men weaving and casting fish nets, people playing and dancing to marimbas and drums, little girls with cornrowed hair playing rhythmic hand-clapping games that I played as a child in New Jersey—each African has thought it was his or her country. I’m not sure they really believed me when I insisted that it was the Pacific coast of South America.

First Human Settlements and Global Blackness in The South Pacific

In 2014 my sense of the global African Diaspora was made more complete and complex by my final milestone journey to date—the South Pacific to the Melanesian Islands of New Caledonia and Vanuatu. I had gotten somewhat acquainted with the region when I attended the South Pacific Arts and Cultural Festival in Papua New Guinea in 1980 and was now curious to see how it fit with the rest of the global African Diaspora.⁵² Arrows on Harris’s map did not guide me to the South Pacific because his map covered only the last two millennia, and this diaspora was much older. But having followed his arrows as far as India, I was intrigued to see what lay farther east.

Melanesia in the South Pacific, half the world away from the Atlantic Ocean and the Atlantic worldview, tends to be ignored in African Diaspora discourse. It is interesting that the three Pacific island clusters are called Micronesia, small islands, and Polynesia, many islands, and that only Melanesia—black islands (Papua New Guinea, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, and Fiji), is named for the melanin-rich skin of the inhabitants. The 19th century nomenclature from the era of the creation of scientific racism offers a key to understanding how the region relates to the rest of the global African Diaspora.

To understand the South Pacific in the context of this diaspora requires a definition that involves both the African origins of humanity and contemporary concepts of Blackness. The peoples of the South Pacific have a much older and very different role in the African Diaspora than the other populations I have gotten to know. Aboriginal Australians and highland Papua New Guineans represent the first enduring settlements of the anatomically modern humans, the ancestors of all humanity, who migrated out of Africa more than 50,000 years ago to begin populating the earth in the first African Diaspora.⁵³ In contrast to Papua New Guinea, which was part of the same land mass as Australia until waters rose and separated them thousands of years ago, the other Melanesian Islands have been inhabited for only several thousands of years. This was still long before the massive diaspora of enslavement of Africans across the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, Sahara Desert, Mediterranean Sea, and Atlantic Ocean of the last two millennia.

One cannot relate this 2000-year-old diaspora to those early diasporas in terms of any kind of historical continuity. The connections are actually contemporary. After being in Australia and Papua New Guinea for fifty millennia, it is understandable that people consider that this is where they have always been, rather than thinking that they came from elsewhere. Melanesians in New Caledonia and Vanuatu told me that their ancestors had been on those islands for perhaps 4,000 years and that they had migrated from elsewhere in the South Pacific, not from Africa.

The key to my understanding came from asking people in New Caledonia and Vanuatu about their relationship to the global African Diaspora, and having them tell me that they had no connection with Africa. But when I would ask how they related to other people of African origin in the world, to other black people, they would say, “Oh, the Black Diaspora. Of course we are Black. Of course we are a part of the Black Diaspora.” So their frame of reference, rather than related to a sense of global Africanity, was rather about a sense of “Global Blackness.”

As an illustration of this identification with Global Blackness, in Australia, the Garvey movement, information about which was shared by African American and Caribbean seamen working alongside Aborigines in Australian ports, became an inspiration for early 20th century Aboriginal movements to secure equal rights. And in the mid-20th century Aborigines found inspiration for seeking greater rights in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, the Black Panther Party, and especially in the teachings of Malcolm X. African American service men on leave from the Vietnam war were a major source of this information.⁵⁴ Thus, descendants of the oldest African Diaspora have been identifying with members of the newest Diaspora as models for their human rights struggle.

In Vanuatu, where many African American World War II soldiers were stationed in construction battalions, they were an inspiration for the Vanuatu independence movement.⁵⁵ And in New Caledonia, where the Melanesian Kanak population has been pushed into the crevices of the society by continued French colonization, young people express their identification with Global Blackness by dressing in clothes featuring images of Bob Marley and making music with a reggae beat.

During the obligatory stopover in Sydney on the way from Los Angeles to the Melanesian islands, I unexpectedly met several Australian South Sea Islanders, a group I had never heard of. I was surprised to find so many different African Diaspora/Black Diaspora communities in the region, with different historical circumstances and current situations. “We are the descendants of slaves,” they said. Thinking that there had not been slavery in Australia, I was confused. Then they said a date that I understood well: 1863!

That was the year when the British started “blackbirding,” taking people they referred to as “blackbirds” from mainly Melanesian islands to Queensland, Australia, to produce sugar. That the date corresponded with the issuing of the U.S. Emancipation Proclamation that freed many enslaved African Americans from producing sugar did not seem like a coincidence. Whereas the South Pacific process was characterized as contract labor, much blackbirding was coercive. Australian South Sea Island descendants of blackbirds now assert that it was a form of slavery.⁵⁶ In addition to seeking reparatory justice from the Australian government, Australian South Sea Islanders have been reconnecting with their families in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. They thus see themselves as part of a forced local diaspora that is relinking with its roots, as well as being part of the Global African/Black Diaspora.

The lesson from this encounter with descendants of the original African Diaspora and with Melanesians whose story as a people began later, but still longer ago than that of the rest of us, is to look at the African presence in the world in terms of both global Africanity and Global Blackness. In that way, the people who represent the first African Diaspora of all humans, who are looking to people from the most recent Atlantic Diaspora for guidance and inspiration in their struggle for their rights, also have their place.

The Global African Diaspora as Sidi Kawandi

My decades of anthropological quests to experience the global African Diaspora began when the Spirit intrigued me in a New Jersey church and have culminated, for now, with my learning about the original African Diaspora in the South Pacific. Not averse to canoes, climbs, or dancing for ancestors, I participated in milestone events that increased my knowledge and broadened my perspectives, and I followed Joseph Harris’s arrows along beaten and unbeaten paths toward places of diasporic participant-observation. I now have a satisfying sense of the global African Diaspora—where it is, who it is, and what it’s doing.

A surprising revelation on this quest was the amazing tenacity with which some African cultural elements remained unchanged after centuries in the Diaspora, such as Juan Garcia’s Br’er Rabbit and David Ayovi’s Mamy Wata stories in Ecuador. Other African elements have been recreated and reinterpreted as they have taken on new life in their new worlds. The way that Kongo/Congo royal culture has been perpetuated in Brazil and Panama is an example. In Brazil, it is expressed in Catholic ceremonies; in Panama it is secular and festive.

In the global African Diaspora, similar themes play themselves out in comparable ways in unrelated geographies. With no obvious historical connections, I observed similarities, for example, between characteristics of the Mlouk of the Moroccan Gnawa and the Orishas of the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé. And a phenomenon experienced in one place inclined me to look for a related one in another. A servis zancet/service for the ancestors on Reunion Island led me to the Garifuna Dugu in Honduras. The Gnawa and Candomblé ceremonies are different in structure, as are the two ancestral ceremonies. But essential elements are the same—percussion-based dancing, ritual meals, costuming, and especially the sacred trance that allows spiritual beings to inhabit their descendants’ bodies to communicate with the human community.

A characteristic inherent to the nature of the global African Diaspora, perhaps the most fundamental one, is the African to African synergies resulting from encounters of Africans with other Africans from different parts of the continent to create new cultural forms in the Diaspora. In Esmeraldas in Ecuador, a musician with a West African name plays an instrument with a Central African name, and a storyteller with the same West African name tells a Central African story. In the Congada in Brazil’s Minas Gerais, a Mozambique kingdom has a Congo queen and Ethiopian saints.

I also found a similar dynamic expressed in a similar way in India and Brazil on opposite sides of the African continent. Like the Brazilian Congada with Saint Benedict, Gujarati Sidis also venerate an Ethiopian saint, Bava Gor. And both Afro-Brazilians and Afro-Indians play instruments with Bantu names from farther south in another cultural area of Africa for their Ethiopian saints from the continent’s northeast. For Bava Gor, Gujarati Sidis play the malunga, a Bantu term for a type of musical bow called berimbau, in Brazil, which has no role in Congada music, but is used in the Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira. Afro-Brazilians play their gomas for Saint Benedict, and the Sidis play their gomas for Bava Gor. The term goma for the Sidis still has the Bantu meanings of drum, rhythm, music, and dance, and refers to both sacred dancing for their saint and secular entertainment and performance dancing. Several Gujarati performance groups, in fact, call themselves Sidi Goma.⁵⁷

The global African Diaspora is, thus, a patchwork quilt, a Sidi kawandi, of African cultural phenomena scattered around the earth and re-assembled in diverse ways in different parts of the Diaspora to form new cultural forms that are sometimes surprisingly similar. Such rich Pan-African reconstructions deserve much more research from a relentlessly global perspective. I have merely skimmed the surface here, and look forward to following more arrows to further diasporic discoveries.

Originally published in the Journal of African American History, Vol. 100, #3, Summer 2015.

NOTES

¹Decade for People of African Descent, 2015–2024. www.un.org

²I. Dugast and M. D. W. Jeffreys, L’Ecriture des Bamum: Sa naissance, son évolution, sa valeur phonétique, son utilisation. Mémoires de l’Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (Yaoundé, Cameroon, 1950); and Christraud M. Geary, Images from Bamum: German Colonial Photography at the Court of King Njoya (Cameroon, West Africa, 1902–1915) (Washington, DC), 1988.

³Abdias do Nacimiento, Africans in Brazil: A Pan-African Perspective (Chicago, IL, 1992).

⁴Olly Wilson, “‘It Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing’: The Relationship between African and African American Music,” in African Roots/American Cultures: Africa in the Creation of the Americas, ed. Sheila S. Walker (Lanham, MD, 2001), 153–168.

⁵Ibid.

⁶For a discussion of concepts of the African Diaspora see Colin Palmer, “Defining and Studying the Modern African Diaspora,” in American Historical Association Newsletter 36, no. 6 (September 1998): 12–15; and “The African Diaspora,” Black Scholar 30 (Fall–Winter 2000): 56–60.

⁷Adrian Miller, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time (Chapel Hill, NC, 2013); Sheila S. Walker, “Everyday Africa in New Jersey: Wondering and Wandering in the African Diaspora,” African Roots/American Cultures, 45–80.

⁸Claude Tardits, Le Royaume Bamoum (Paris, 1980).

⁹Sheila S. Walker, Du Roi Njoya à la Diaspora Africaine Mondiale: Un Témoignage d’une Africaine- Américaine,” in Le Roi Njoya: Créateur de Civilisation et Précurseur de la Renaissance Africaine, ed., Hamidou Komidor Njimoluh (Paris, 2014), 181–188.

¹⁰Sheila S. Walker, Ceremonial Spirit Possession in Africa and Afro-America: Forms, Meanings, and Functional Significance for Individuals and Social Groups (Leiden, Netherlands, 1972).

¹¹Abdelhafid Chlyeh, Les Gnaoua du Maroc: Itinéraires Initiatiques Transe et Possession (Paris, 1998).

¹²Ibid.

¹³Sheila S. Walker, Les divinités africaines dansent aux Amériques et au Maroc, La Transe, ed., Abdelhafid Chlyeh (Marrakesh, 2000), 13–32.

¹⁴Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men: Negro Folktales and Voodoo Practices in the South (New York, 1935); Their Eyes Were Watching God (Greenwich, CT, 1937); and Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica (New York, 1938).

¹⁵Katherine Dunham, Island Possessed (New York, 1969); and Journey to Accompong (1946).

¹⁶Melville Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (New York, 1941).

¹⁷Sheila S. Walker, The Religious Revolution in the Ivory Coast: The Prophet Harris and the Harrist Church.

(Chapel Hill, NC, 1983).

¹⁸Carol V. R. George, Segregated Sabbaths: Richard Allen and the Emergence of Independent Black Churches, 1760–1840 (New York, 1973).

¹⁹George Bond, Walton Johnson, and Sheila S. Walker, eds., African Christianity: Patterns of Religious Continuity (New York, 1979).

²⁰Primer congreso de la cultura negra de las Americas, Cali, Colombia (Bogotá, Colombia, 1988).

²¹Joseph E. Harris, Global Dimensions of the African Diaspora (Washington, DC, 1982).

²²Joseph E. Harris, The African Presence in Asia: Consequences of the East African Slave Trade (Evanston, IL, 1971).

²³Joseph E. Harris, The African Diaspora, map, 1980.

²⁴Sheila S. Walker, “The Feast of Good Death: Celebrating Emancipation in Brazil,” in Women in Africa and the African Diaspora: A Reader, ed. Rosalyn Terborg Penn and Andrea B. Rushing (Washington, DC, 1996), 203–214; “The Saints versus the Orishas in a Brazilian Catholic Church as an Expression of Afro-Brazilian Cultural Synthesis in the Feast of Good Death,” African Creative Expressions of the Divine, ed. K. Davis and E. Farajaje-Jones (Washington, DC, 1991), 84–98; “A Choreography of the Universe: The Afro-Brazilian Candomble as a Microcosm of Yoruba Spiritual Geography,” Anthropology and Humanism Quarterly 16, no. 1 (June 1991): 42–50; and “Everyday and Esoteric Reality in the Afro-Brazilian Candomble,” History of Religions: An International Journal for Comparative Historical Studies 30, no. 2 (November 1990): 103–128

²⁵Elizabeth W. Kiddy Blacks of the Rosary: Memory and History in Minas Gerais, Brazil (University Park, PA 2005); Linda Heywood, Central Africans Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora (Cambridge, UK,

2002); and Sheila S.Walker, “Congo Kings, Queen Nzinga, Dancing Devils, and Catholic Saints: African/African Syncretism in the Americas,” in Héritage de la Musique Africaine dans les Amériques et les Caraïbes, ed. Alpha Noel Malonga and Mukala Kadima-Nzuji (Brazzaville, Congo, and Paris, 2007) 125–132.

²⁶The convention is to spell the Kongo kingdom with a “K” and the two contemporary Congo republics as well as Congo phenomena in the Americas with a “C.”

²⁷Renee A. Craft, When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in Twentieth Century Panama (Columbus, OH, 2015).

²⁸“Argentina: People and Ethnic Groups,” Encyclopedia Britannica, www.britannica.com, 2015.

²⁹Romero Jorge Rodríguez, “The Afro Populations of America’s Southern Cone: Organization, Development, and Culture in Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay,” in Walker, ed., African Roots/American Cultures, 314–331.

³⁰Walker, ed., African Roots/American Cultures; and Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora (film, Afrodiaspora, Inc., 2011, 2015).

³¹The Durban Declaration and Programme of Action, www.un.org.

³²Sheila S. Walker, ed., Conocimiento desde adentro: Los afrosudamericanos hablan de sus pueblos y sus histo- rias (Popayan, Colombia, 2013).

³³Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Swimmers and Divers in the Atlantic World,” The Journal of American History (March 2006): 1327–1355; and “Swimming, Surfing, and Underwater Diving in Early Modern Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora,” in Navigating African Maritime History, ed. Carina Ray and Jeremy Rich (St. Johns, Newfoundland, Canada, 2009), 81–116.

³⁴Shihan de S. Jayasuriya and Richard Pankhurst, eds., The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean (Trenton, NJ, 2003); and African Identity in Asia: Cultural Effects of Forced Migration (Princeton, NJ, 2009); and Amy Catlin- Jairazbhoy and Edward A. Alpers, eds., Sidis and Scholars: Essays on African Indians (Trenton, NJ, 2004); Beheroze Schroff, Director-Documentary films: Voices of the Sidis: “We’re Indian and African” (2004); and Voices of the Sidis: Ancestral Links (2006); Sidis of Gujarat: Maintaining Traditions and Building Community (2011); Voices of the Sidis: The Tradition of the Fakirs (2011).

³⁵Beheroze Schroff, “Spiritual Journeys: Parsis and Sidi Saints” in Journeys and Dwellings: Indian Ocean Realities in South Asia, ed. Helene Basu (New Delhi, India, 2008), 256–275; and “Sidis in Mumbai: Negotiating Identities between Mumbai and Gujarat,” African and Asian Studies 6, no. 3 (2007): 305–319.

³⁶Harris, The African Presence in Asia.

³⁷Henry John Drewal, “Aliens and Homelands: Identity, Agency and the Arts among the Siddis of Uttara Kannada,” in Catlin-Jairazbhoy and Alpers, Sidis and Scholars: Essays on African Indians, 140–158.

³⁸Ababu Minda Yimene, African Indian Community in Hyderabad: Siddi Identity, Its Maintenance and Change (Cottbus, Germany, 2004).

³⁹Ibid.

⁴⁰Pashington Obeng, Shaping Membership, Defining Nation: The Cultural Politics of African Indians in South Asia (Lanham, MD, 2008).

⁴¹Kenneth X. Robbins and John McLeod, African Elites in India: Habshi Amarat (Ocean Township, NJ, 2006).

⁴²Ibid.

⁴³Kiran Kamal Prasad and Jean-Pierre Angenot, eds., TADIA: The African Diaspora in Asia: Explorations on a Less Known Fact (Bangalore, India, 2008).

⁴⁴Alexandre Popovic, La Révolte des Esclaves en Iraq au IIIe/IX Siècle (Paris, 1976).

⁴⁵Georges Collinet and Sheila S. Walker, producers, UNESCO Slave Route Project, Slave Routes: A Global Vision (Paris, 2010).

⁴⁶Prosper Eve, Les Esclaves de Bourbon: La Mer et La Montagne (Saint-Denis, Reunion, 2003).

⁴⁷H.U.E. Thoden Van Velzen and Ineke Van Wetering, In the Shadow of the Oracle: Religion as Politics in a Suriname Maroon Society (Long Grove, IL, 2004).

⁴⁸Françoise Dumas-Champion, Le Mariage des Cultures à l’Île de la Réunion (Paris, 2008).

⁴⁹Joseph O. Palacio, ed., The Garifuna, A Nation Across Borders: Essays in Social Anthropology (Belize City, Belize, 2005).

⁵⁰Jean-Michel Deveau, L’Or et les Esclaves: Histoire de Forts du Ghana du XVIe au XVIIIe Siècle (Paris, 2005). Charles R. Boxer, The Golden Age of Brazil, 1695–1750 (Berkeley, CA, 1969); and Raymond E. Dummett, El Dorado in West Africa: The Gold-Mining Frontier, African Labor, and Colonial Capitalism in the Gold Coast, 1875–1900 (Athens, OH, 1999).

⁵¹Dummett, El Dorado in West Africa.

⁵²Sheila S. Walker, A Festival Reflection on Faces, Places, Paradise (Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, 1981).

⁵³Georgi Hudjashov, Toomas Kivisild, Peter A. Underhill, Phillip Endicott, Juan J. Sanchez, Alice A. Lin, Peidong Shen, Peter Oefner, Colin Renfrew, Richard Villems, and Peter Forster, “Revealing the Prehistoric Settlement of Australia by Y Chromosome and mtDNA Analysis,” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. PNAS published online 11 May 2007, www.pnas.org; and Morten Rasmussen et al., “An Aboriginal Australian Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia,” Science 334, 94 (2011): 93–98.

⁵⁴Alyssa L. Trometter, “Malcolm X and the Aboriginal Black Power Movement in Australia, 1967-1972,”

Journal of African American History 100 (Spring 2015): 226–249.

⁵⁵Marcelin Abong, Interview, Kaljoral Senta, Port Vila, Vanuatu, 24 July 2014.

⁵⁶Clive Moore, “The Pacific Islanders’ Fund and the Misappropriation of the Wages of Deceased Pacific Islanders by the Queensland Government,” Australian Journal of Politics and History, 61 1 (2015): 1–18. doi:10.1111/ajph.12083; and Reid Morgensen, “Slaving in Australian Courts: Blackbirding Cases, 1869–1871,” Journal of South Pacific Law 13, no. 1 (2009), accessed 2 July 2015.

⁵⁷Ibid.

About the Author

Sheila S. Walker

Dr. Sheila S. Walker Ph.D, cultural anthropologist and filmmaker, is Executive Director of Afrodiaspora Inc., a non-profit organization that is developing documentaries and educational materials about the global African Diaspora. She has done fieldwork lectured consulted and participated in cultural events in much of Africa and the African Diaspora. Her most recent works are the documentary films Familiar Faces/Unexpected Places: A Global African Diaspora, Slave Routes: A Global Vision for the UNESCO Slave Route Project and an edited book Conocimiento desde adentro: Los afrosudamericanos hablan de sus pueblos y su historia (Afro-South Americans Speak of their People and their Histories) featuring articles by Afrodescendants from all of the Spanish-speaking countries of South America. She also edited the volume African Roots/American Cultures: Africa in the Creation of the Americas and produced the documentary Scattered Africa: Faces and Voices of the African Diaspora. Dr. Walker was Director of the Center for African and African American Studies the Annabel Irion Worsham Centennial Professor in the College of Liberal Arts and Professor of Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin and she was the William and Camille Cosby Professor in the Humanities and Social Sciences Professor of Anthropology and Director of the African Diaspora and the World Program at Spelman College. Learn More