A Brief Introduction to Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, a small country on the southwestern coast of West Africa, is among the most diverse in Africa. It is home to descendants of peoples from throughout sub-Saharan Africa, as well as over fourteen ethnic groups. Sierra Leone received its rather poetic name from Portuguese explorer Pedro da Cintro, who dubbed it Serra de Leão, meaning “Lion Mountains” when he visited the port at modern-day Freetown in 1462. The country became independent in 1961, after being a British colony for 150 years. Its tropical climate supports a diverse environment, ranging from savannah to rainforest. It is the only country on the western coast of Africa whose terrain boasts hills that rise from the sea, which makes for a spectacular coastline.

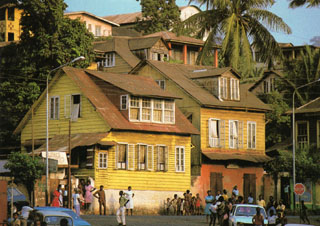

Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, is the country’s social, cultural, and economic epicenter, as well as the seat of the country’s multiparty democratic government. Sierra Leone’s early inhabitants were the Sherbro, Temne, and Limba peoples. Today, the Temne—believed to have come from Futa Jallon in present-day Guinea—predominate in the Northern Province and the Western Area. The Mende—believed to be descendants of the Mane from Mali—predominate in the southeastern provinces. The third-largest ethnic group are the Limba, who originated in Sierra Leone’s Wara Wara mountains. Other ethnic groups include the Fula, Mandingo, Kuranko, Loko, Susu, Kissi, and Yalunka. Although ethnic heritage is a main source of personal identification for many Sierra Leoneans, intermarriage among ethnic groups is common.

Today, Sierra Leone’s vast cultural diversity also results from the aftermath of the Atlantic slave trade, of which Sierra Leone was an early hub. In 1792, Freetown was founded by the Sierra Leone Company as a home for formerly enslaved African Americans seeking repatriation to Africa. Over the course of the next century, these “Liberated Africans” formed the Krio community, whose language—a pidgin of English and several indigenous African languages—now dominates throughout Sierra Leone. In 1808, Freetown became a British Crown Colony; in 1896, the British declared a protectorate over the rest of Sierra Leone. The country thus became a single entity with a shared history and culture. English would ultimately become the official language. Later immigrant populations arrived and stayed for the economic and educational opportunities they found during the independence era.

This incredible diversity lends itself to a vast range of languages, cultural expressions, and customs–and despite the country’s recent history of conflict, these ethnic and religious groups coexist peacefully in Sierra Leone. The culture—or cultures—of Sierra Leone have been ingrained in its peoples and adapted to the changing global environment over the course of many centuries. It is not surprising, then, that the country’s cultural and educational accomplishments have been myriad over the course of its history. Once referred to as the “Athens of Africa,” Freetown is home to the oldest Western-style university in Africa (Fourah Bay College, founded in 1827) and, for much of the 20th century, it attracted political and educational leaders from throughout Africa.

Sierra Leone’s artistic culture also garnered acclaim: in 1964, the Sierra Leone National Dance Troupe, founded by internationally-recognized John Akar, won first prize for their performance at the World’s Fair in New York City. The conservation of this rich cultural diversity is especially crucial in Sierra Leone’s postwar era, as the country still struggles to overcome the effects of the devastating civil war that lasted from 1991-2003. The effects of the civil war are undeniable: the conflict left tens of thousands dead; it left hundreds of thousands displaced, maimed, or orphaned; it destroyed much of the nation’s operational, cultural, and economic infrastructures; and it disintegrated the deep-seeded social structures of many of the nation’s communities, leaving a growing population of youth largely disconnected from the social fabric that previously defined their cultural and national identities.

Nevertheless, despite the harsh realities of Sierra Leone’s recent history, it is troubling that narratives of conflict so often overshadow the nation’s deep cultural heritage, which defined and guided many generations—a fact that young Sierra Leoneans are increasingly aware of. The time is ripe for cultural programs such as the CCP, which present invaluable opportunities for Sierra Leone to celebrate its national heritage; to rally diverse communities around the revival of national cultural values and expressions; and to engage the country’s youth as they prepare to lead their communities toward a unified, peaceful future.